A Lovers Tryst

Two lovers meet in secret. Gazing across the grassy Delph, they dare not speak for fear of discovery, they dare not touch for fear of the terrible consequences. This silent meeting takes place every day for many weeks until one day, at the end of April, the young man stands there alone. Although he returns often she does not come again. He is fraught with worry but he cannot go seek her at her home. His name was Rowland Torre of Stoney Middleton, her name was Emmott Sydall and she lived in the village of Eyam.

I visited the sleepy village of Eyam (rhymes with stream) on a dank and misty day in February. The village nestled beneath damp green hills and was encircled by the shiny black branches of winter trees – the whole landscape seemed drenched in silence and mystery. I would almost say there was a mournful air to the place, but that would be to over simplify the incredible story of this village and the terrible sacrifice its inhabitants chose to make.

Signs and Portents

They said that Plague was a punishment from God visited on the sinful, and that it should be borne with fortitude and prayer. The seventeenth century had seen a world turned upside down with regicide, the commonwealth and the restoration bringing religious, political and economic turmoil in their wake. But by the 1660’s things had calmed, Charles II was on the throne, the village of Eyam was thriving with a rich lead mining industry, busy yeomen farmers and tradesmen plying their trades. But the signs were there all the same…

They said that village lads had allowed the cows to stray into the churchyard, the nave had been fouled; soon after unnatural white crickets were spied on hearths; the Gabriel hounds were heard calling on the moors: God was displeased with Eyam. Or so the faithful reasoned when plague arrived as an unwanted guest a year later.

The Plague

The Plague has been known in Europe since the mid fourteenth century. Its first terrible outbreak in the late 1340’s wiped out up to one-third of England’s population. In the intervening years there were many sporadic outbreaks across Europe. It was not until the early twentieth century that the cause of the plague was discovered to be bacillus carried by fleas and transmitted to Black Rats and thence (when there were not enough rats to support the fleas) to humans.

The Bubonic Plague was spread by black rats who lived in very close proximity to humans (in the wainscot, in the thatch, under your floor). You could expect vomiting, high fever, extreme pain, gangrene in the extremities, swellings of the lymph glands, particularly in the groin. These swellings were excruciatingly painful, large and often burst.

“The pain of the swelling was in particular very violent and to some intolerable; physicians and surgeons may be said to have tortured many poor creatures, even into death.” So wrote Daniel Defoe in his ‘Journal of the Plague Year’.

The Pneumonic Plague was even more virulent as a flea bite was not required in its transmission – it was spread by the coughs and sneezes from its victims. Pneumonic plague affected the blood and lead to extreme fluctuations in temperature which usually lead to coma and death.

During the three hundred or so years when the Plague visited and revisited Europe, people had few defences against it. Nostrums and charms both Christian and more pagan varieties were employed. Sweet smelling nosegays were used to ward of noxious plague filled air; fires were burned in the streets to disperse the infected miasma. Some of the cures on offer were unorthodox to say the least – tying a chicken or a toad to the buboe to draw off the poison; poultices made up of varying degrees of foul ingredients. Preventative measures were taken such as killing cats and dogs who were mistakenly seen as responsible for spreading the plague; and most disturbing of all the immuring of whole families where plague had visited a household, effectively condemning sick and healthy alike to a slow and painful death. Some advice was sound: leave the infected area, however this also facilitated the spread of the disease.

Plague comes to Eyam

1665 saw the plague raging in London but the remote village of Eyam would seem far away from the problems of the capital. But plague, like bad news, travels fast. Legend has it that sometime in August or September 1665 a bundle of cloth was sent from London (some say Canterbury) to a travelling tailor lodging with Mrs Cooper of Eyam.

Records suggest that Mrs Cooper was a relatively affluent widow, and possibly a merry one as she married a second time in March of 1665. Her new husband Alexander Hadfield may have been the travelling tailor referred too in local legend but he was away from home at the time of the plague (not returning until much later). It is likely that he had an apprentice or a servant by the name of George Viccar’s whose fate was to be the first victim of the plague. Dr Richard Mead, writing in the eighteenth century and using the recollections of Mompesson’s son described the scene thus:

“a box of materials relating to his trade [was delivered] a servant [George Viccars] who opened the aforesaid box, finding they were damp was ordered to dry them by the fire.”

Perhaps he loosed fleas from the cloth or perhaps flea eggs hatched in the warmth of the fire, what ever he let loose George Viccars paid the price and died within the week. The second victim was young Edward Cooper Mrs Cooper’s son. Over the next few days close neighbours began to fall ill and die: Peter Hawksworth, Thomas Thorpe and his 12-year-old daughter. It couldn’t have taken long for the villagers to realise that something was terribly wrong.

The deaths continued through the late summer and autumn, those who had means, such as the wealthy Sheldon family, fled. Those who were tied to their trade or land, or simply too poor or too late to flee remained. Some camped in the hills and caves in the surrounding area but many stayed in the village. Those who camped nearby might have made the best decision – in fleeing the outbreak they had left behind the insanitary conditions that helped spread the plague.

Plague comes in the summer, preferring the warmer months of the year so there was a falling off of deaths during the winter. Numbers began to creep up again in spring 1666, and by April there had been 73 deaths (well above the average for a village of Eyam’s size). May saw a lull and the villagers hoped for the best. Medical knowledge of the day said there should be a clear gap of 21 days with no new infections before an area could be deemed clear of plague. Eyam was not so lucky.

By June many more had fled – the Rector William Mompesson had sent his children to safety in Yorkshire although his consumptive wife Catherine had insisted on remaining by his side to help tend the sick, although it would cost her life (she died in August and was buried in the churchyard by special dispensation). It was clear that action needed to be taken in order to prevent plague spreading beyond the village. In the absence of the usual village hierarchy who had mostly fled, the Rector became the focus of authority in the village. However, village life was never simple and the rector was a young man and a newcomer to the village. He needed an ally in order to successfully carry out any action, and he found it in Thomas Stanley the former incumbent.

Thomas Stanley was a puritan who replaced the traditionalist and unpopular rector during the civil war. The old rector was re-established in 1660, but Stanley remained a part of religious life in the village and was very popular. Mompesson took the rectorship in 1664 but Stanley’s influence must still have been very strong in the village. Nevertheless despite their widely differing views both were able to put aside these differences in order to present a united front to the village. This unity undoubtedly helped in gaining their parishioners consent to the radical plan the men proposed.

A Simple Plan

1. No more burials in the churchyard – people would bury their own dead on their own land or gardens.

2. The Church would be closed and services would be held out-of-doors at Cucklet Church, in the Delph, with family groups remaining at least 12 feet apart from their neighbours (sound advice).

3. The village would be quarantined. No one would leave or enter the village until it was clear of plague in order to prevent it spreading to neighbouring villages and towns such as Bakewell, Fulwood and Sheffield.

The villagers entered into a pact with their Rector and consented to the quarantine, knowing full well that for many of them it was a death sentence. Nevertheless their religious faith fortified their resolve – many felt it was their religious duty to seek divine forgiveness, some went to the extreme of refusing the cures on offer for fear of offending God.

It is hard to understand how terribly these simple rules would have affected the villagers. It is harder still to imagine the suffering that was to come: whole families were wiped out, people were forced to bury their own dead, inscribe their own headstones when even the mason died. The infected, whilst still living, would have heard their own graves being dug in preparation. But death would bring no respite because at that time it was held that if a person was not buried in consecrated ground they would not rise on Judgement Day and be reunited with loved ones in paradise. That was the extent of the sacrifice the villagers were prepared to make to prevent plague spreading.

Staying alive

Despite the bleak outlook, in the midst of death, life still goes on. Practical measures were implemented to alleviate suffering. The Earl of Devonshire paid for food and medical supplies and local villages supported Eyam by supplying goods which were dropped off and paid for at set points around the boundaries of the Cordon Sanitaire. Many of these drop off points remain today as poignant reminders of this time. In order to disinfect coins left by the villagers they were usually left in water – Monday Brook earned its name at this time when goods from Bakewell’s Monday market were exchanged there. The Boundary Stone has niches drilled in it that were filled with vinegar to disinfect the coins and Mompesson’s Well sits on a lonely stretch of the Grindleford Road.

Of death and life

The death toll was huge, Mompesson stated 76 families were affected. Some of the monthly figures show the devastation of the plague: July 56 deaths, August 78, September 24, October 14.

However, statistics can never truly convey the human cost of plague, individual families suffered huge losses: Jane Hawksworth lost 25 members of her immediate and extended family; The Talbot’s and the Hancock’s were all but wiped out: Mrs Hancock burying her husband and 6 children in the space of a week before eventually fleeing Eyam. The graves she dug can still be seen, and have become known as the Riley Graves, they stand as a silent testament to one woman’s almost unimaginable loss.

Not everyone who contracted plague died, some survived and their stories have entered local folk-lore. Margaret Blackwell was in the final stages of plague when suffering from a raging thirst she swigged back a jug of bacon fat mistaking it for milk. She vomited up the fat and made a remarkably swift recovery, convinced that the bacon fat had saved her. Another case has a certain macabre humor about it – Marshall Howe himself a plague survivor thought he may have built up some immunity so offered his services (for a fee) to help bury the dead. One such client was a man called Unwin, and as Marshall dragged the corpse towards its grave, he was horrified to hear the dead man call for a drink. Marshall fled in terror thinking the dead had risen.

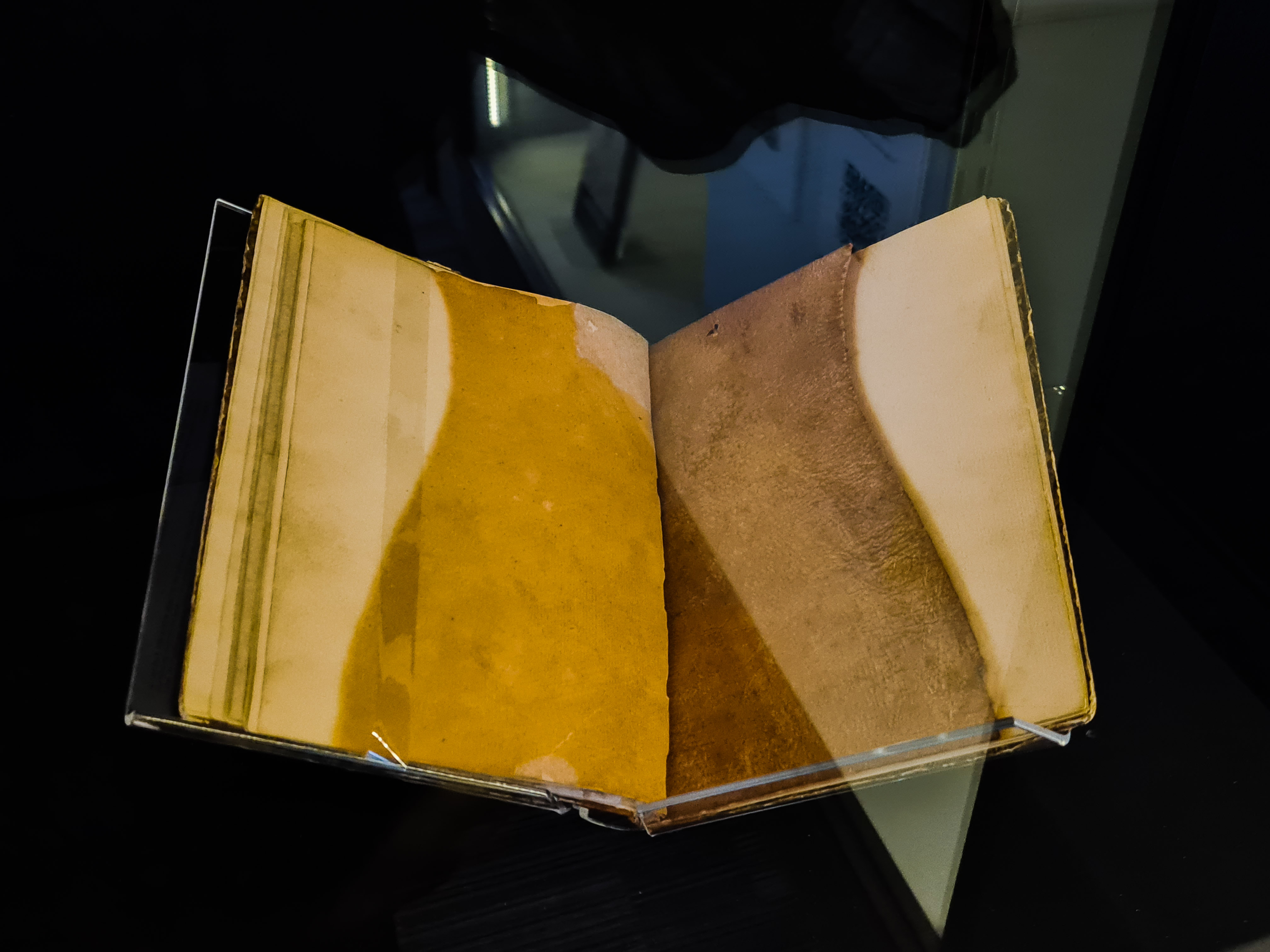

Finally by Christmas 1666 Plague was officially over and the villagers began to return to their homes. One final action was required to ensure plague was gone for good and, lead by the Rector himself, villagers burned all but the clothes on their backs.

And what of Emmott and Rowland? Rowland was one of the first outsiders to enter the village once the quarantine was lifted. When he found the Sydall house empty his hopes must have begun to fade. He soon discovered that the Sydall’s were all dead and that his precious Emmott had fallen ill and died shortly after their last meeting. All his months of waiting and hoping had been in vain.

In all close to 260 villagers of Eyam died in the outbreak which lasted for 14 months. But they had succeeded in their plan – the plague did not spread beyond Eyam.

Today Eyam is a working village, but it has never forgotten its extraordinary history. The Parish Church commemorates events in a stained glass window, and Eyam Museum provides historical detail.

Every year, at the end of August a commemorative service is held at Cucklet Church, in the Delph, to remember those who made this sacrifice.

Sources

BBC – Legacies, http://www.bbc.co.uk/legacies/myths_legends/england/derby/article_1.shtml

Clifford, John, ‘Eyam Plague 1665 – 1666’, 2003 edition

Eyam Museum, https://www.eyam-museum.org.uk/

St Lawrence Eyam Parish Church, spanglefish.com/EyamChurch/index.asp?pageid=14206

All links were correct at the time the article was published.

Leave a Reply