Stelliana

“…if she had been in those times when men committed idolatry, the world would certainly have renounced the sun, the stars and all other devotions and with one consent have adored her for their goddess.”[1]

As an acknowledged beauty of the Stuart Age, with a slightly suspect reputation, it was to be expected that scandal and gossip clung to Venetia Stanley’s name. However it was her mysterious demise – which led to suggestions of suicide and allegations of murder, and the obsessionally morbid devotion displayed by her husband after her death, that would ensure her lasting fame.

Sexual adventuress or secret bride?

Venetia Stanley had had an effect on men from the moment she was born. She was born in 1600, in Tong Castle in Shropshire, into a well-connected family. Her father was Lord Edward Stanley and her mother Lady Lucy Percy, co-heiress to the vast Percy fortune. When Lucy tragically died, Lord Stanley had the young Venetia sent away rather than have her presence a constant reminder of his lost love, Lucy.

Growing up in the countryside, at Enston Abbey in Oxfordshire [2], the young Venetia’s star burned bright. Gossipy polymath John Aubrey, writing several decades after Venetia’s death, wrote of her early life:

“..it seems her beauty could not lie hid. The young Eagles has espied her, and she was sanguine and tractable, and of much suavity (which to abuse was a great pittie)”[3]

I’m no expert on the idioms of seventeenth century speech but it sounds rather like Aubrey is suggesting that the young Venetia might just have been a bit of a flirt.

After Oxfordshire, she decamped to London where she continued to make a stir everywhere she went. In the debauched Stuart Court beauty was everything and young Venetia had it all – perfectly meeting the ideal of the Stuart age with her fine dark locks, alabaster complexion, languid ‘come to bed’ eyes, and as Aubrey so nicely puts it, her ‘bona roba’, her curvaceous figure.

The Stuart Court was a place of great sexual license, but barring one or two privileged exceptions (such as the notorious Countess of Somerset) that license tended to be issued to men only: randy cavaliers could bed whom they pleased with little fear of tarnishing their reputation. The sexual politics of the time was not quite so tolerant of female rakes; money and social standing could offer some protection to a young adventuress but gossip and scandal could be cruel bedfellows. Venetia was not immune to slander, both during her life and even decades after her death.

Aubrey, generally the most quoted source for her life, claimed that Venetia was the mistress of Richard Sackville, Earl of Dorset, and had children by him. In his Brief Lives, Aubrey states that Sackville paid her £500 annually – no mean sum. However, Aubrey is not necessarily the most reliable source, writing decades after her death and often reporting gossip and hearsay as fact. Another possibility is that Venetia’s reputation as a courtesan may be in part due to the fact that her marriage to Sir Kenelm Digby in c1625 was kept secret until after their first child was born [4].

The Ornament of England

Kenelm was the son of Sir Everard Digby who was executed following the Gun Powder Plot. He was a scholar, philosopher, courtier,alchemist, privateer, and general all round clever-dick given the somewhat pompous epithet “the ornament of England”.

“Sir Kenelme Digby was held to be the most accomplished cavalier of his time. [..] He was such a goodly handsome person, gigantique and great voice, and had so gracefull Elocution and noble address, etc., that had he been drop’t out of the Clowdes in any part of the World, he would have made himself respected. But the Jesuites spake spitefully, and sayd ’twas true, but then he must not stay there above six weeks.’”[5]

I can’t help but think that Aubrey seems to take sly delight in spiking this unctuous description with a little acid.

Theories as to why the pair might have kept their marriage a secret abound: from Sir Kenelm’s mother disapproving of her prospective daughter-in-law’s libertine life-style or considering her a penniless gold-digger to fears that Venetia would be cut off from her father’s will should she marry against her family’s wishes.

Whatever the truth behind the rumours, Sir Kenelm appears to have loved Venetia deeply and she him. He commissioned many portraits of Venetia, both during her life and after her death. One such portrait entitled ‘Chastity crushing Cupid’ – could be perhaps interpreted as a bit of PR for his wife’s reputation as a sexual adventuress. Aubrey suggests Sir Kenelm was well aware of the gossip surrounding his wife’s (lack of) virtue and claims he said “..a wiseman, and a lusty could make an honest woman of a brothell-house” [6]. For a man who went on to write incessantly about his love for Stelliana, aka Venetia, in his Private Memoirs, it would seem quite a harsh thing for him to say of her.

Even Aubrey concedes that Venetia transformed from mad-for-it party girl to virtuous wife and mother with ease. However the slight twist in the tale of the stolid church-going matron. Venetia was an avid, and it would seem, successful gambler, and it is alleged she funded many of her good works through her winnings…so perhaps a little of the wild-child remained after her marriage.

Lead Powder and Viper Wine

Several years of happy and uneventful marriage ensued, Venetia and Sir Kenelm had four sons and seemed ready to slide into comfortable middle age. Hermione Eyre, author of Viper Wine, a novel about Venetia, suggests that far from being a time of placid contemplation of impending old age, Venetia may have found the transition from youth to middle age extremely difficult.

As a celebrated beauty seeing her charms fade as the years passed, living in a society that judged women on their looks (sound familiar, anyone?), she could easily have fallen back on cosmetics and potions in a desperate bid to preserve her looks.

Certainly the fashionable women (and men) of the Stuart Court were not shy about slapping on the make-up. Pale complexions and acres of bare bosoms were enhanced and perfected with ceruse a mixture of finely ground lead powder and vinegar. A tracery of pale blue veins might be drawn on to imitate the translucent skin of youth, a lead comb could darken the eye brows. Spanish wool, or Spanish paper (a cloth impregnated with cochineal) was used to colour the lips and cheeks [7] and all of this could have been held in place with a varnish of egg white. The look would seem to be porcelain doll… with a whiff of omelette…

Ladies might go further than the surface and could take any number of miracle beauty preserving potions…such as Viper wine…filled with such hearty ingredients as baked viscera of vipers (yummy) such concoctions could claim near miraculous effects:

“This quintessence is of extraordinary good virtue for the purifying of the flesh, blood and skin” and “preserves from grey hairs, renews youth, etc” [8]

As Hermione Eyre points out, ladies regularly using lead as their cosmetic of choice would quickly ruin their complexions and must have been willing to try pretty much anything to improve them. Venetia was certainly a big fan of Viper wine and had been drinking it, so Aubrey claims, at the behest of her husband for a number of years.

Sleeping Beauty….is dead

On the morning of the 1 May 1633 Lady Digby’s maid entered her bed chamber to wake her mistress for her morning ride. Sir Kenelm had spent the night tinkering in his laboratory until the early hours, he had slept there rather than disturb his wife. It was he who was disturbed however, by “That shrill and baleful sound expressing her heavy plight struck my eares.” when the maid screamed in horror upon finding her mistress dead in her bed. She was only 33.

Sir Kenelm was distraught, Venetia lay in her bed exactly as she had laid down to sleep the night before, a faint blush on her cheek, looking as though she might wake up at any moment. What he did next may seem strange…he called an artist. Within two days of Venetia’s death he had Sir Anthony Van Dyck (1599 -1641) come and sketch the corpse of his wife, as it lay, in her bed. He also had casts taken of her head, hands and feet.

Portrait of Death: Lady Digby on her Deathbed

Sir Anthony Van Dyck’s portrait is either tender and seductive, or slightly creepy and stalker-ish depending on your view-point. Portraits of the newly deceased were not unheard of in the Stuart Age, and later, the Victorians were famous for their morbid family portraits of dead relatives. But from a modern perspective at least, the realisation that the subject is in fact dead, is enough to jar the senses and the sensibility. In the modern age we have become so separated from death and the dead, seeing their images mainly in news footage and usually connected with violent or tragic events. This is different, this is not a celebration of the corpse, or a quick snap-shot for the family album, it is a meditation upon death. Sleeping beauty has entered into that long good night that beckons us all.

Suicide, Murder or Misadventure?

Even in the seventeenth century, an age when death came regularly to the young and apparently healthy, suspicions were raised about Venetia’s sudden and mysterious demise. Poison was suspected but was it suicide, murder or over indulgence in viper wine? Aubrey reports that gossips said:

“Spiteful women would say it was a ‘viper husband’, who was jealous of her, that she would steal a leap.” (have an affair).

There was also the curious suggestion that Digby was given a letter by the maid, just before Venetia’s death, in which Venetia had enclosed paper that might be of interest to him…what that paper may have been has never been discovered [9].

An autopsy was ordered by Royal Command, and the famously rotund Dr Theodore de Mayerne was called in. Digby insisted she had always been healthy, but did take Viper wine for headaches. Upon opening her head the good doctor found “but little brain” and it has been inferred from that, that the cause of death may have been a cerebral haemorrhage. However due to the time that elapsed before the autopsy was carried out it is likely that the results may have been invalid [10]. Hermione Eyre proposes the theory that the viper wine itself may have killed Venetia. She showed the recipe to a doctor who said:

“this type of “beauty potion” usually works, if it works, by blocking the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, which can be toxic in the wrong doses. “Hence ‘deadly’ nightshade,” he said. Viper Wine’s herbal elements – not the snakes, which are incidental – could have been used to dilate the pupils, vasodilate the cheeks leading to a healthy blush, and promote euphoria, but if she drank too much, it could have been fatal.” [11].

So was it suicide, murder or misadventure? Personally I don’t think she committed suicide, she was a devout Catholic, attending Mass daily. She would surely have regarded suicide as a sin and a bar to heaven. I don’t think the evidence supports the theory that that Sir Kenelm poisoned her. His eccentric and obsessive behavior after her death does not necessarily mean a guilty conscience, it could just have been how he coped with the such a devastating and unexpected loss. On balance, I like the viper wine theory proposed by Hermione Eyre. If not the Viper wine specifically, one of the other deadly cosmetic ingredients could easily have been the silent killer in this case. However after the passage of time, and the possibility that Venetia simply had some underlying medical condition, it would seem that the true cause of Venetia Stanley’s death will likely never be proven.

Epilogue

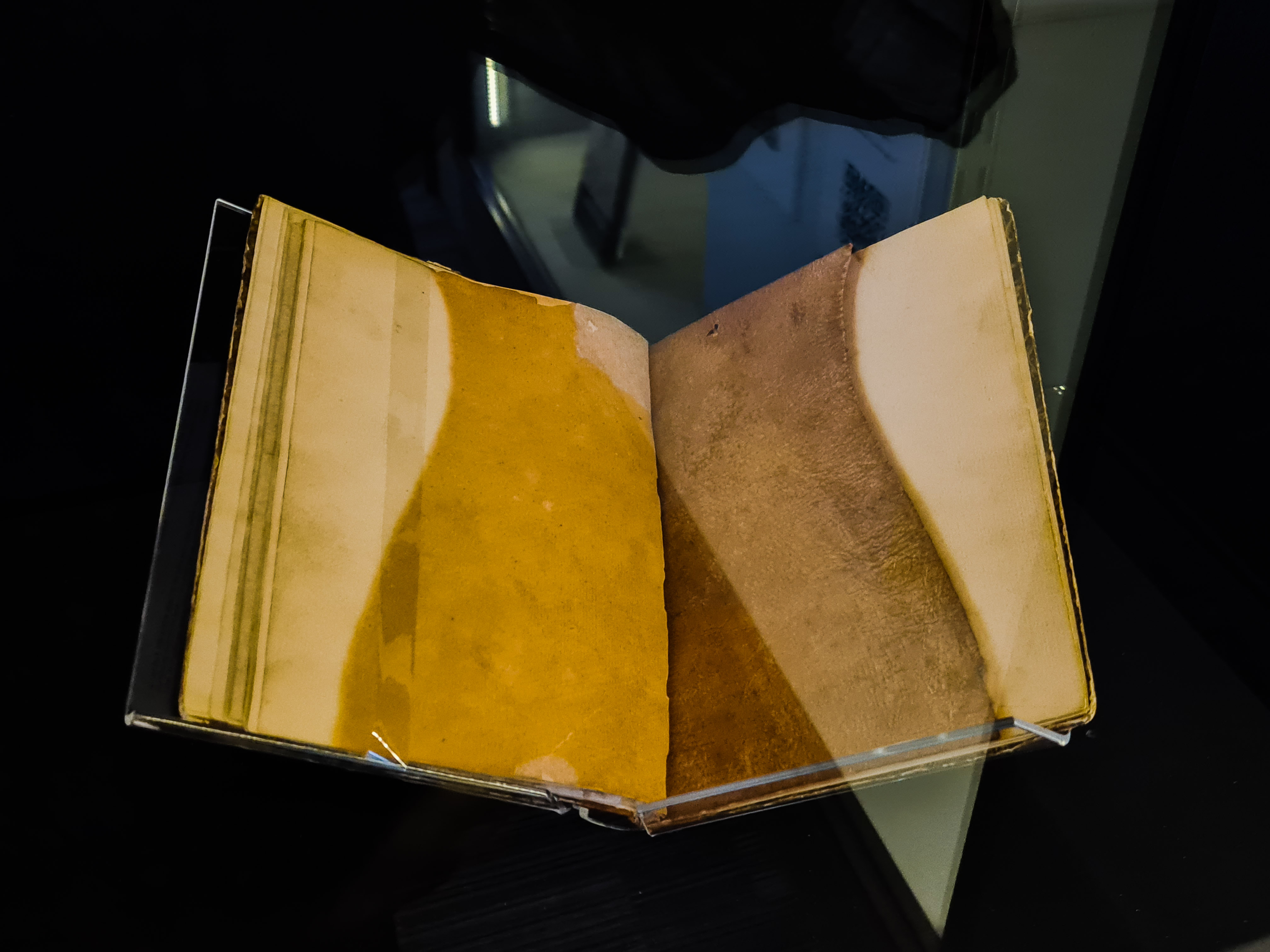

The final word should perhaps go to Sir Kenelm, unable to forget the beautiful wife whose sudden death shook his world to the foundation, he retreated to Gresham College and led the life of a scholarly hermit. He kept the portrait with him for many years, until he lost it during English Civil War.

“This is the onely constant companion I now have…It standeth all day over against my chaire and table …and all night when I goe into my chamber I sett it close to my beds side, and by the faint light of the candle, me thinks I see her dead indeed.” [12]

Sources and notes

Aubrey, John, Brief Lives, available online via Gutenberg Press [1] [3] [5] [6]

Digby, Sir Kelemn, Private Memoirs/Stelliana available on Google Books [2]

Downing, Jane, 2012, Beauty and Cosmetics 1550 – 1950, Shire Library [7]

dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/explore-the-collection/151-200/venetia,-lady-digby,-on-her-deathbed/

telegraph.co.uk/history/10680346/Venetia-Stanley-did-viper-wine-kill-the-17th-century-beauty.html [8] [10][11]

Leave a Reply