Normal for Norfolk

Norfolk is a strange place at the best of times: a famously flat county dotted with windmills, flint cottages and churches; a land of salt-marsh, sea and sky. Perhaps some of its strangeness comes from the fact that over the centuries much of the land was reclaimed from the sea – land which the sea still coverts. A place on the margins of sea and land would seem primed for folk-lore and legends, yet it is not as famous for its folklore as, say, the west country.

Norfolk is densely packed with churches and ruined religious houses, as well as hosting the famous Pilgrimage site at Walsingham. Nevertheless, despite the ubiquity of the church in the county’s history and landscape, there are still many strange folk-tales and legends ingrained in the lore of the county. From ominous black dogs, to admonitory sprites and determined mermaids. Here is a very brief journey through some of those tales.

Black Shuck

Black dogs abound in British folk-lore, many counties boast their own version of this phantom hell-hound: Guytrash, Trash and Barghuest are but a few of the names it goes by, depending upon the county or region in question. Even Essex’s famous witch village, Canewdon, boasts a ghostly black dog. However, it is Norfolk’s lanes, churchyards, salt-marshes and coastal paths, for my mind, which are the natural home of Old Shuck. Historically, the county also had a thriving smuggling trade, and smugglers were not averse to ‘encouraging’ such beliefs if it made their covert exploits easier to manage by keeping the idle and the curious indoors of a night-time.

Oft described as the size of a calf, this shaggy dog with glowing red saucer eyes, would silently stalk – or even directly confront – the solitary traveler wending his way along a lonely road at dusk. Sometimes Old Shuck drags a chain, sometimes he is headless; occasionally he comes as a guardian or protector, but most often his presence forebodes ill to the witness and legend says that they, or their kin, will die within a twelve-month.

‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’ by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, published initially in serial form in The Strand Magazine between 1901-1902, helped introduce the idea of the Phantom Hound to a wider public. Although the story is set on Dartmoor, and is most likely based on a Devonshire legend relating to one Richard Cabell [1], Conan Doyle did stay for a while at Cromer Hall in Norfolk. An estate which encompassed a lane supposedly the haunt of Black Shuck – so there is a slim possibility that this may also have proved some inspiration for his famous story.

The origins of the name have been attributed to the Old English Scucca, meaning Devil or fiend [2] or perhaps a Norfolk dialect word ‘shucky’ meaning ‘shaggy’ or ‘hairy’ [3]. As descriptions often refer to the shaggy nature of this particular cryptid or para-canine (as the author of the very informative Shuckland website prefers to call it), this would seem a fairly logical theory.

Some much has been written on Black Shuck that it is impossible to do justice to the subject in so few words, there are excellent websites out there devoted entirely to Old Shuck. However one cannot avoid presenting the most famous cases of ‘Death by Shuck’ on record…

The Churches at Bungay and Blythburgh in Suffolk, were visited by both a terrifying electrical storm and a terrifying para canine, on the 4 August 1577. Death and destruction followed. The London-based Reverend Abraham Flemming, in his ‘A Straunge and Terrible Wunder’ provided the Tabloid version of events, based second-hand tales (which the locals might just have embroidered – a tad – with each re-telling…)

“This black dog, or the divil in such a linenesse (God hee knoweth al who workesth all,) running all along down the body of the church with great swiftnesse, and incredible haste, among the people, in a visible fourm and shape, passed between two persons, as they were kneeling uppon their knees, and occupied in prayer as it seemed, wrung the necks of them bothe at one instant clene backward, in somuch that even at a mome[n]t where they kneeled, they stra[ng]gely dyed.” [4]

Another unfortunate parishioner was left horribly burned. Famously, scorch marks were left on the church door and were ever after called ‘the devil’s fingerprints’.

Later that day the storm, and the Shuck, reached a church at Blythburgh with similarly deadly consequences.

It has been suggested, quite reasonably, that the fierce electrical storm, occurring at the same time as the appearance of the hell-hound, is the most likely reason for all the death and destruction (especially when the burn injuries of the survivors are considered). That, combined with the traumatic religious upheavals of the day, might have led the superstitious people of the parish to translate such a terrible catastrophe, caused in a church (surely the safest place they could possibly be), to be caused by a malign supernatural agency. [5] It may have made the tragedy easier for them to process.

The interest in Black Shuck persists even now, on a recent visit to Norfolk I picked up an entertaining contemporary supernatural thriller, ‘Black Shuck’ by Piers Warren. Set in the salt-marshes around Blakeney Point, the novel successfully evokes the strangeness and remoteness of the North Norfolk coastline, creating a perfect setting for Black Shuck. Warren uses a version of the Shuck legend that explains Shuck as the loyal dog of a drowned sea-captain, doomed to spend eternity searching the coastline for his lost master. While his hound isn’t entirely sympathetic, and is in fact, very much in need of some serious Barbara Woodhouse treatment, it is one of the alternative explanations of the Black Shuck. To see black dogs as demonic hell-hounds, or manifestations of Old Nick himself is not the whole story. Perhaps Black Shuck is as doomed as those he encounters, perhaps he is just the bearer of bad news and not its cause. It can’t be much of an after-life for a loyal hound – becoming a terrifying harbinger of doom.

Hyter Sprites

The most mysterious and elusive Norfolk beastie seems to be that of the Hyter Sprite (also known as hikey, hykry, hikra and ikry sprite)[6]. Rather like Shuck, their name may originate in Old English which contains the word ‘hedan’, or perhaps, the Saxon word ‘Hodian’. Both broadly meaning ‘to heed, guard, keep’ or to ‘take notice’/’give attention too’ [7]. This rare sprite is found in Eastern Norfolk and the North Norfolk coast. Most commonly appearing as an admonition to children – ‘if you go out on your own after dark, the hyter sprites will get you’ they are associated with nightfall, woodland and marshes. Mostly used to encourage children to be safe and behave, with a mild threat implied that the hikeys will get them if they don’t, they do not seem particularly dangerous or foreboding, unlike the often menacing Old Shuck.

They are a creature rarely sighted and with no clear description to fit. The most famous, and likely misleading, description being that given by Dr Katherine Briggs in her 1973 Encyclopaedia of Fairies and based on information provided by Ruth Tongue:

“Hyter Sprites. Lincolnshire and East Anglian fairies. they are small and sandy-coloured with green eyes like the Feriers of Suffolk. The assume the bird form of sandmartins. They are grateful for human kindnesses and stern critics of ill-behaviour [..]the hyter sprites have been known to bring home lost children, like the Ghillie Dhu of the Highlands.” [8]

Others have envisioned them as bat-like creatures. But always as protective spirits who warn children from danger and were possessed of had bird-like qualities. However not all descriptions were so favorable, one tale collected by Daniel Allen Rabuzzi during his researches found an alarming description provided by the aged aunt of one informant – the protective little hyter sprite was transformed into ‘a spindley-legged light-footed blooksucker’ that haunted the salt-marshes and kept locals safely in their cottages at night….no doubt much to the benefit of local smugglers.

Oddly enough, there is no definitive description of a hyter sprite. In fact, Rabuzzi comments that in comparison the many recorded sightings of the supernatural beastie, Black Shuck, there appeared to be few if any recorded sightings of hyter sprites. This lead him to the conclusion that they were not in any sense a fully fledged fairy folk tradition, but rather were ‘heeder spirits’ that represented a ‘folk-expression’. Primarily used to admonish children and discourage them from taking risks, rather than creating any real expectation of an actual encounter. A bit like a mildly threatening Easter bunny (and distinctly preferable to spindle-legged blood-suckers, in my mind at least).

The Mermaid of Upper Sheringham

Oddly enough, although considered freakish, mermaids were actually thought to exist within nature, certainly during the medieval period and even beyond (a belief that the showman Barnum famously capitalized on, in the 19th century).

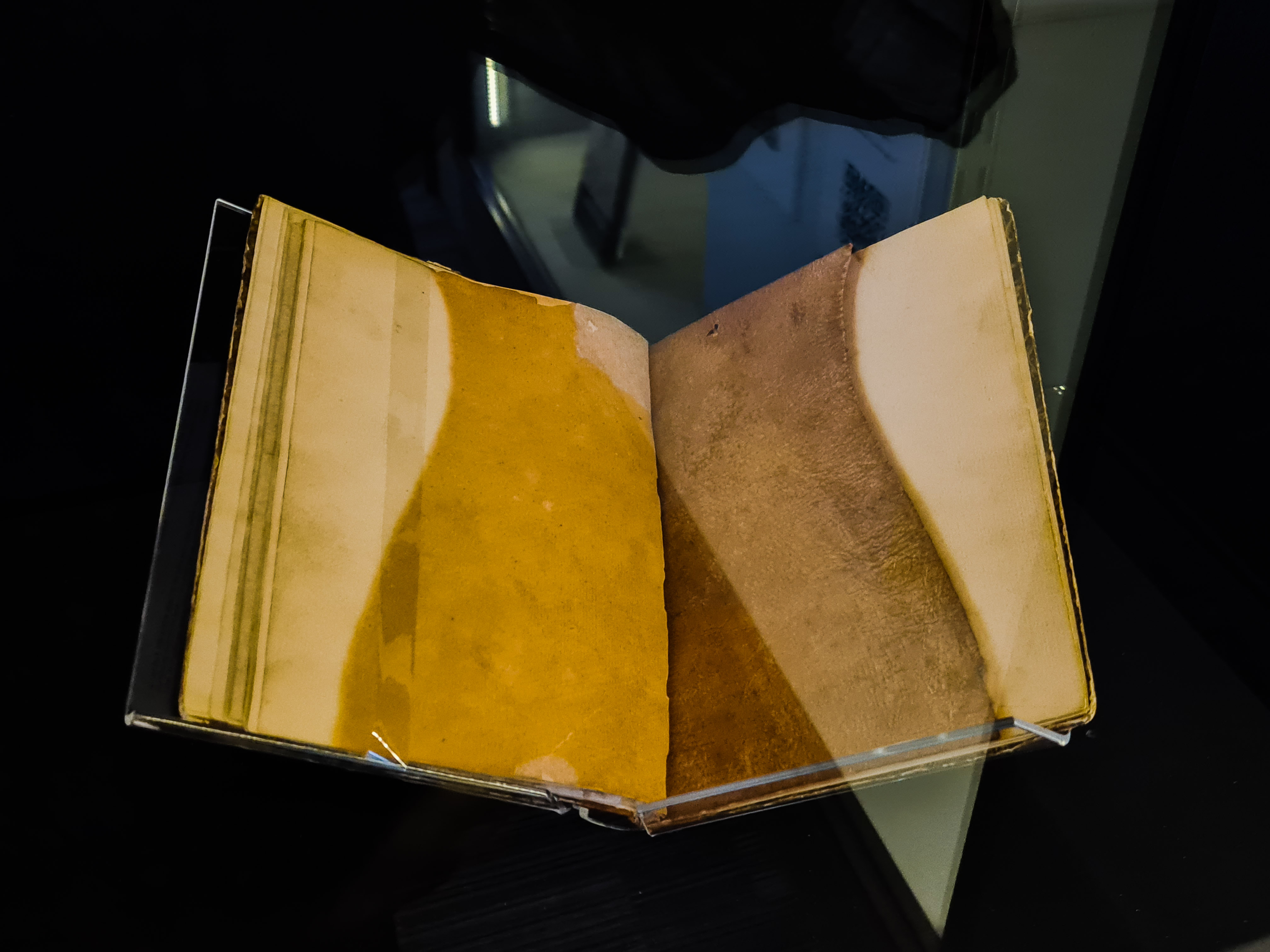

No coastal village would be complete without at least one Mermaids tale… and the small fishing village of Sheringham is no different. A mile or so up the hill from the bucket and spade paradise of Sheringham, is the quieter village of Upper Sheringham. In the 14th century village church, All Saints, is the remnant of a very fishy tale indeed.

The pews in the church date from the 15th century, and the bench ends contain many a fantastical beastie, but one in particular draws the visitor, the pew by the north door is adorned with a somewhat stocky and rather burly mermaid. Looking distinctly unsiren-like this mermaid is commemorated with an inscribed tale which goes something like this:

A mermaid decided to visit the parish church at Syringham (Sheringham) and managed to flip and flap her way from the seashore, up the hill to All Saints church in the village of Upper Sheringham. Some say she came seeking a soul, and so, with her goal almost in sight, she pushed open the north door of the church. A service was in progress and the beadle, seeing a slippery siren trying to gain admission, somewhat unchivalrously slammed the door in the unfortunate fish lady’s face, exclaiming ‘Git ew arn owt, we carn’t hev noo marmeards in ‘are!’

Not to be deterred – mermaids may suffer from a bit of a bad reputation at times, but they are descended from an Assyrian goddess after all – the mermaid bided her time, and when a suitable opportunity arose, she pushed open the north door of the church and slithered into the pew at the back of the church. And here she remains to this day. Whether she gained a soul – or was truly in want of one – nobody knows.

Mermaids, despite their divine ancestry suffered from very bad PR during Christian times, often being used as a symbol of vanity and sexuality, prostitution and earthly vices. It has been suggested that perhaps the little mermaid in All Saints could commemorate an unwelcome visit to the church by a prostitute [9] however appealing this interpretation is, personally I think it is more likely just down to the imagination of the medieval carver – either coloured by local lore or on the order of the parish priest, to illustrate a moral tale.

From the ill-omened supernatural cryptid, Old Shuck, to the pseudo real creatures mermaids, and the heeder spirit folk-expression that is the hyter sprite, Norfolk would seem as rich in folk traditions as it is in medieval churches.

Sources and notes

Images – all images copyright Lenora unless otherwise stated.

http://www.fairyist.com/fairy-types/hikey-sprites/

http://norfolkcoast.co.uk/myths/ml_blackshuck.htm [9]

http://www.norfolkcoast.co.uk/myths/ml_mermaid.htm

Pickering, David, ‘Cassell’s Dictionary of Superstitions’ Cassell

Rabuzzi, Daniel Allen, ‘In Pursuit of Norfolk’s Hyter Sprites’ Folklore vol.95 No.1 (1984), pp 74-89 (available on JStor) [2] [6] [7] [8]

Simpson, Jacqueline and Round, Steve, ‘Oxford Dictionary of English Folklore’ Oxford, 2000

http://www.hiddenea.com/shuckland/introduction.htm

Timpson, John, ‘Timpson’s Norfolk Notebook’, Acorn, 2001

Trubshaw, Bob, ‘Black dogs in folklore’ At the Edge archive http://www.indigogroup.co.uk/edge/bdogfl.htm

Warren, Piers, Black Shuck http://www.wildeye.co.uk/black-shuck/index.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Shuck [3] [4] [5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Hound_of_the_Baskervilles [1]

Leave a Reply