Evil Clowns

Coulrophobia – the fear of clowns. From fictional phantoms such as Stephen King’s Pennywise to serial killer John Wayne Gacy’s alter-ego Pogo the Clown, and even the current trend for ‘killer clowns’ sweeping the US and UK, clowns have developed a somewhat sinister reputation of late. Their painted faces and over-sized clothes intended to convey innocent humour can, to some people, appear both uncanny and disturbing. But evil killer clowns are not an entirely modern phenomenon – if the stories about Thomas Skelton, the last jester of Muncaster Castle – are to be believed. Thomas Skelton is thought by some to be the original Tom Fool from Shakespeare’s King Lear, but his ‘Last Will and Testament’ may hint at a much darker side to this comedian.

Who was Thomas Skelton?

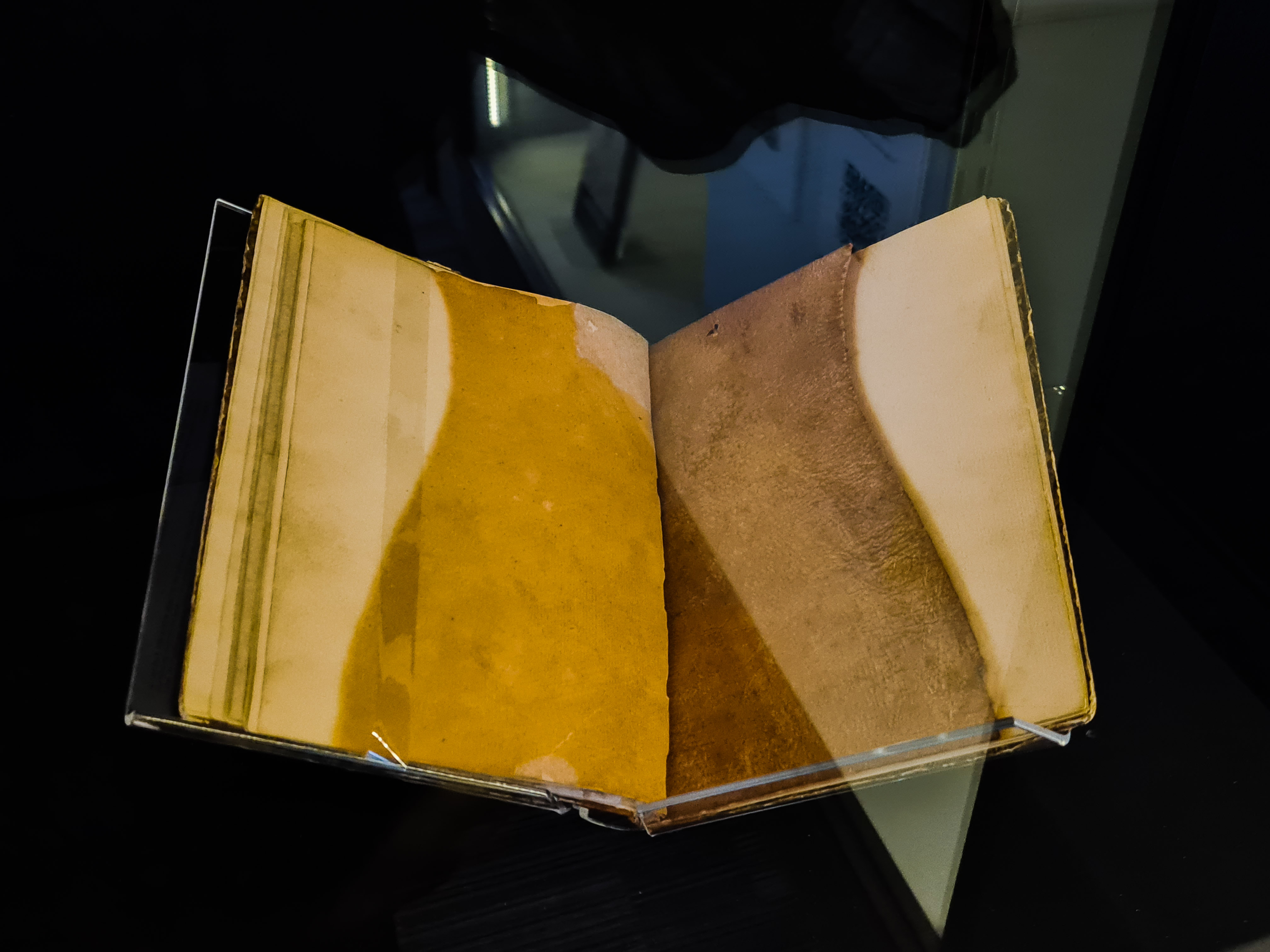

Thomas Skelton is famous for being the last jester of Muncaster Castle, a stately pile near the village of Ravenglass, Cumbria, in the north-west of England. We know this because he is the named subject of a famous full length portrait that hangs in the castle. The picture depicts a ruddy-faced middle-aged man, dressed in jester’s motley, holding a staff of office in one hand, and a document written in doggerel, attested to be his will, hangs beside him.

Thomas Skelton last jester of Muncaster Castle. Image via BBC website.

That a portrait was painted of a family retainer must indicate that he was a beloved family servant. His attire is masterfully comic – his patchwork robe, staff of office and scroll and mock privy seal all act to parody the pompous badges of office of high officialdom, and rather than listing his titles and achievements the scroll offers up what purports to be Tom Fools last will and testament. He even mocks the noble gallant, with the name of his lady pinned into his hatband, aping the fashions of the day, whilst wearing his jesters motley.

Interestingly, the portrait at Muncaster Castle isn’t the only portrait of Tom Skelton. EW Ives in his article for the Shakespeare Survey [1] focuses his research on a second portrait, purchased by the Shakespeare Society in 1957 from the Haigh Hall Collection of the Earls of Crawford and Balcarres. It is by examining this portrait and the text of the will, that EW Ives has attempted to pin-point exactly when and where Tom Fool lived.

Dating Tom Fool

Ives uses references to well-known local individuals named in the will, cross checked with burial records from Wigan, to build a picture of the movements and the dates for Tom Skelton. He proposes that although Tom Skelton was originally the jester at Muncaster Castle, upon the death of Lord Pennington, Tom accompanied the young heir when he was sent to live with his relatives, the Bradshaugh’s, at Haigh Hall in Wigan. At Haigh Hall, sometime between 1659 – 1665, a portrait of Tom was painted. Sir Roger Bradshaw’s wife was a Pennington, and may have known Tom Fool as a child. Ives suggests that when the heir reached his majority and wished to return to Muncaster, he wanted to take the portrait of the much-loved jester with him. As Tom Fool had been a well-loved family servant, at both Muncaster castle and Haigh Hall, a copy of the portrait was commissioned to remain at Haigh Hall (possibly completed in the 1680’s) while the original returned with the heir to Muncaster. Ives states that there is no evidence that Skelton returned to Muncaster after 1659, while the young heir was away, so it would seem likely Tom died at Haigh Hall [2].

The current incumbent of Muncaster Castle, Peter Frost-Pennington, confirms that evidence for Thomas Skelton’s life in the historical record is hard to find. He was, after all, just a servant, even if he was one esteemed enough to have his likeness captured in oils. Frost-Pennington keeps his margins wide quoting ‘1600 give or take 50 years’ [3], a possible references to him comes from a letter dating to the reign of Henry VIII, while another could put him as far back as the late fifteenth century. However if the research by EW Ives is correct, then unfortunately Tom Skelton could not be the model for Shakespeare’s Tom Fool in King Lear which dates from about 1605/6.

A Killer Sense of Humour

There were two mains types of fool or jester, the natural fool – one with a physical or intellectual disability; and the artificial fool – an entertainer or comedian. Fools and jesters were often part of a royal court or noble family and by virtue of their position could often speak harsh truths to their ‘betters’ in the guise of drollery. Shakespeare often uses the fool as the voice of common sense and wisdom, in Twelfth Night the jester is remarked to be ‘wise enough to play the fool’ [4] It is not clear from the scant historical record, or the portrait, which kind of fool Tom Skelton was, but whether natural or artificial, some of his favourite antics have come down to us.

Like many fools and jesters, Tom was a valued and trusted servant of the Pennington family, entertaining them with a mixture of practical jokes and wit. He is famed for such clownish antics as cutting off a branch while he sat upon it; greasing up banisters on the staircase to annoy guests, then when asked who was responsible, quipped that he thought ‘everyone had a hand in it’.

However things take a more sinister turn in the anecdotes relating to Tom Skelton reported in ‘The Remains of John Briggs a compilation of tales and essays’ published in the Westmorland Gazette and Lonsdale Magazine in 1825.

Briggs relates what purports to be oral tradition surrounding a murder committed by Thomas Skelton at the behest of one Sir Ferdinand Hoddleston, of Millum Castle. It all began when Helwise, the lovely daughter of Sir Alan Pennington of Muncaster Castle, had disguised herself as a shepherdess and attended the May Day festivities in order to meet her secret lover, Richard the Carpenter. Wild Will of Whitbeck, a local ruffian, had fancied his chances but was rejected by Helwise. To get his revenge on the lovers he spilled the beans to Sir Ferdinand (yet another wannabe suitor for Helwise).

Angered at losing out to a humble carpenter, Sir Ferdinand went to Muncaster Castle bent on informing Sir Alan Pennington of his daughter’s low connection. However as chance would have it, first he met with Tom Fool, aka Thomas Skelton, and had the following conversation in which Tom recounted a nasty trick he played on ‘Lord Lucy’s Footman’. This seems to have given Sir Ferdinand an idea of Tom’s homicidal potential…

“‘he asked me’ said Tom, ‘if the river was passable; and I told him it was for nine of our family had just gone over. – They were geese’ whispered Tom; ‘but I did not tell him that.-the fool set into the river, and would have drowned, I believe, if I had not helped him out’”.

Briggs goes on to recount that Tom also had a personal grudge against Dick the Carpenter –

“‘[..]I put those three shillings which you gave me into a hole, and I found them weezend everytime I went to look at them; and now they are only three silver pennies. I have just found it out that Dick has weezend them.’

‘Kill him Tom, with his own axe, when he is asleep sometime – and I’ll see that thou takest no harm for it.’ Replied Sir Ferdinand.

‘He deserves it, and I’ll do it,’ said Tom.

[..]

And the next day while the unsuspecting carpenter was taking an after dinner nap, and dreaming probably of the incomparable beauties of his adorable Helwise, Tom entered the shed, and with one blow of the axe severed the carpenters head from his body. ‘There,’ said Tom to the servants,’I have hid Dick’s head under a heap of shavings; and he will not find that so easily, when he awakes, as he did my shillings.’”

The conclusion of this unhappy tale was that heartbroken Helwise entered a nunnery, while the vengeful Sir Ferdinand met a bloody death fighting the Earl of Richmond (Henry Tudor) at Bosworth Field [5]. Which frankly, seems to place this tale much to early to be attributed to the seventeenth century Tom Skelton.

Other tales claim that Tom Fool would sit under a chestnut tree outside Muncaster Castle, watching travellers go past. Should any traveller ask him for directions, they were at risk of being misdirected to dangerous quicksands near the River Esk [6]. May people consider that his will makes oblique reference to this murderous pass-time.

‘But let me not be carry’d o’er the brigg,

Lest fallin I in Duggas River ligg;’ [9]

Some tales even have Tom recovering the bodies, decapitating them and burying them under tree trunks.

All of this would seem to paint a picture of an evil and conscienceless individual. But is there more to this than meets the eye? The north-west of England was for hundreds of years,a remote and dangerous place. Blood feuds, rough justice and robbery with violence were part and parcel of everyday life. Could these local folk tales and stories have elided themselves onto half remembered anecdotes of the jolly japes and crude practical jokes of Thomas Skelton? In the Middle Ages there was a tradition in the Tarot of showing death in the garb of the Fool, death having the last laugh (of course) and some traditions also associate the Fool with the trickster and with vice [7&8]. Could these earlier darker traditions, coupled with bloody local legends have become associated with the portrait of Tom Skelton. Once the immediate family who knew him died out, the portrait, with its slightly menacing air could easily have attracted macabre tales in a similar way that some Screaming Skull legends may have developed.

The punchline…

Tom Skelton was the last jester of Muncaster Castle, and probably of Haigh Hall as well. Jesters fell out of fashion with the restoration of Charles II to the throne (and I can’t imagine the puritans would have had much use for Jesters either!) During his lifetime Skelton appears to have been a much valued family retainer, so much so that not one but two portraits were commissioned of him. Even now, his legend as an entertainer has been revived, and Muncaster Castle hosts an annual Jester Competition in honour of Tom Skelton.

But was Tom Skelton the original Tom Fool from Shakespeare’s King Lear? Well probably not, the dating evidence seems to be against it. And more pressingly, was Skelton an evil killer clown? His troubled spirit is said to haunt Muncaster Castle to this day – his heavy tread and the sound of a body (the unfortunate carpenter?) being dragged up the stairs have been reported by several witnesses…is he doomed to walk the earth for eternity re-living his heinous crimes? On that, I will leave you to make up your own mind.

If you want to view the portrait of Thomas Skelton you can visit Muncaster Castle, they even offer paranormal ghost tours so you might even get to meet him….

muncaster.co.uk/castle-and-gardens/castle-overview/

Sources and notes

BBC Cumbria, ‘Muncaster Castle jester competition reveals dark past’ [3] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cumbria-22704190

Bob, ‘The History of the Fool’ foolsforhire.com/info/history.html

Briggs, John, The remains of John Briggs, Kirkby Lonsdale, Foster, 1825 available via https://archive.org/stream/remainsofjohnbri00brigiala#page/154/mode/2up/search/jester [5]

Ives, E.W. ‘Tom Skelton – A Seventeenth-Century Jester’ , Shakespeare Survey 13, 1960 (partial article available via Google books) [1] [2]

Jadewik, ‘A Little Bit of Tom Foolery’, the Witching Hour, 2011 https://4girlsandaghost.wordpress.com/tag/tom-foolery/ [1] [2]

Jones, Paul Anthony, ‘Tom Skelton: The Serial Killer Court Jester’, 2015, http://mentalfloss.com/article/68443/tom-skelton-serial-killer-court-jester [6]

Lipscombe, Suzannah, ‘All the Kings’s Fools’, History Today, 2011 http://www.historytoday.com/suzannah-lipscomb/all-king%E2%80%99s-fools

Mason, Emma, ‘Playing the fool: Tudor jesters’, History Extra, 2015 http://www.historyextra.com/feature/playing-fool-tudor-jesters

Past Presented, ‘Tom Skelton’s Foolish Will’ http://www.pastpresented.ukart.com/eskdale/tomfool3.htm (includes full text of the will) [1] [2] [9]

Leave a Reply