Unraveling the thread of time

On 6 March 2016 the North of England was witness to the eerie dance of the Northern Lights in the night sky. Not often seen so far south, the phenomena was perfectly timed almost coinciding, as it did, with the 300th Anniversary of the execution of James Radcliffe. The Third Earl of Derwentwater was executed on 24 February 1716, at Tower Hill in London, for his part in the doomed Jacobite Rising of 1715. Perhaps the lights were a ripple in time, a reminder that it was as the coffin of the doomed Earl was born home to Dilston, that the same Aurora Borealis was witnessed in the north as a sign of heaven’s displeasure at Radcliffe’s death, and became known as Lord Derwentwater’s Lights.

Francis Dunn, a servant of the Earl’s aunt, witnessed the phenomena at the time, and wrote:

‘A most Beautifull glory appeard over ye hearse, wch all saw, sending forth resplendant streams of colours to ye east & west, the finest yt ever I saw in my Life. It hung like a delicate rich curtain & continued a quarter & half of an hour over ye hearse. There was a great light seen at night in several places & people flockt all night from durham to see ye corpse. Its remark’t yt att ye same day & hour ye glory appear’d over my lord’s hearse, ye most dreadfull signs appeared over London.’ [1]

In fact, in the 300 years since the Earl of Derwentwater died under the headsman’s axe, his shade, and that of his wife, has become part of local lore in and around Dilston and Northumberland. In 1888 The Reverent Heslop writing in the Monthly Chronicle, claimed the Earl did not rest quiet in his tomb:

“The Hall is behind us, and its tragic story haunts the place. it is but a generation since the trampling hoofs and the clatter of harness was heard on the brink of the steep here, revealing to that trembling listener that ‘the Earl’ yet galloped with spectral troops across the haugh. Undisturbed, as the reverent hands of his people had laid him and his severed head, the Earl himself had rested hardly in the little vault for a whole century; yet the troops have been seen by the country people over and over again as they swept and swerved through the dim mist of the hollow of the dene.”

But not only the Earl is said to frequent the ruins of Dilston and Devil Water, his tragic bride is also bound to the castle in death. The story goes that the Earl was a reluctant rebel, and upon setting out with his troop, turned one last time to view Dilston Hall and his vast estates. His resolution wavered as he considered that should the rising fail, he would not only be risking himself, but the future prosperity of his young son and heir. With that thought, he turned for home. However, in the courtyard of Dilston, the Earl was met by his young and implacable wife who proceeded to berated him, going so far as to strike him with her fan, whilst exclaiming ‘take that, and give your sword to me.’ [2] With those words she condemned her husband to his terrible fate, and the Earldom of Derwentwater to eventual destruction. After the young Earl’s death, she too died young and heartbroken; her tormented shade is said to flit between the tall tower of Dilston Castle and Dilston Chapel, lighted cresset in her hand, awaiting the return of her dead lord.

But local lore and legend may have dealt harshly with the Countess and her hesitant husband….

The Jacobite cause in a nutshell

The seventeenth century was a time of great political, social and religious upheaval in England. When Charles II died in 1685 without issue, his brother James inherited the throne. James was raised an Anglican but became a catholic, and after the religious turmoil of the past century, that made people nervous. James’s autocratic style of rule didn’t make him many friends and when his second wife gave him a son in 1688, assuring a catholic succession, parliament made its move.

Parliament turned to James’s protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch husband William of Orange, offering them the crown jointly, thus triggering the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688 which ousted James II. In replacing James II, the de jure king of England (King by right/divine or otherwise), with King William, the de facto (King by possession of the office) the Jacobite cause was born.

When William and Mary died without issue, James’s other protestant daughter, Anne, took the throne. Anne died without issue in 1714 and the throne of England was set to pass to a distant German princeling, George, elector of Hanover. This was almost too much, not only for the catholic Jacobites, but also for many high church Tories in England – the stage was now set for a dangerous rebellion [3 & 4].

The Radcliffes of Dilston Castle and the Stuart Connection

![Lady Mary Tudor - the Stuart connection. Public Domain[?]](https://i0.wp.com/hauntedpalaceblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/mary-tudor_countessofderwentwater.jpg?resize=236%2C381&ssl=1)

The North had always been viewed by the south as a hotbed of Catholicism and potential unrest and measures were taken to curb the powers and resources of Catholics in the area. In Northumberland the most prominent and wealthy catholic family was the Radcliffe family of Dilston Hall, near Corbridge. In the seventeenth century the Radcliffe’s had successfully married into the Stuart Royal family – albeit on the wrong side of the sheets. The 3rd Baronet of Derwentwater, Francis, engineered the marriage of his son Edward to the Lady Mary Tudor, the natural daughter of Charles II, in 1688. The Radcliffes were now fatally linked to the doomed house of Stuart.

The marriage brought an Earldom with it, granted by James II shortly before his overthrow, but it was not a successful marriage. Nevertheless they had four children, the first James, being born on 28 June 1689.

The Radcliffe’s Stuart links were further cemented when the teenage James was sent with his brother Francis, to live with their royal cousin James III (James II having died in 1701) at the court in exile at St Germain in France. In 1705, while James and Francis were still in France, their father died leaving James, at only 16, the third Earl of Derwentwater.

In 1709 Queen Anne allowed the young Earl to return to England and take up his responsibilities. After a brief stay in London, James set off in February 1710 to view his northern estates for the first time. He seems to have made a good impression on the locals, he was after all, young, fashionable and rich. But more than that, he was described as possessing a charming smile and a generous nature – qualities which more than made up for his shortness of stature. During this initial stay he fell in love with Dilston and decided to build a grand new hall befitting his status as third Earl of Derwentwater. In the meantime the Earl made his presence felt in the area, entertaining his neighbours and cousins such as the Erringtons of Beaufront and Swinbournes of Capheaton.

Early on James’s Jacobite sympathies were recognised by his neighbours, and in 1710 he was invited to Lancashire to meet with other gentlemen Jacobites who regularly met at the Unicorn Inn in Walton-le-Dale. Eventually he became Mayor of this group. Whether this was an honorary title, or something that required active engagement, it indicates that he took an keen interest in the Jacobite cause at an early stage. However, it is important to note that at this time there was a genuine hope that Queen Anne would name James III as her heir, thereby providing a peaceful resolution to the problem of the king over the water. James Radcliffe, cousin and childhood companion of James III, must have hoped as much. After all, as one of the richest men in the North, he would have much to lose if it came to an uprising [5].

For a while things went smoothly for the young Earl, he married Anna Maria Webb, a pretty catholic heiress, in 1712 and moved away from Dilston for a few years while the new hall was constructed. His heir John was born in 1713, and soon after Dilston Hall was completed, allowing Radcliffe family to return. But things were not going so smoothly elsewhere…. Queen Anne sickened and died in 1714, and King George I’s reign looked set to entrench the power of the Whigs, the Jacobites and Tories grew fractious, riots and unrest soon broke out in London….

Oak Leaves and White Roses

History records that the Jacobite Rising of 1715 began on 6 September, when John Erskine 11th Earl of Mar raised the Stuart standard in Braemar. That the Jacobite Risings were largely Scottish affairs has entered the popular imagination, however there were many in England who felt sympathy for the king over the water. Catholic or not, he was the rightful heir and in a time when belief in the divine right of kings had not yet evaporated, that could count for a lot. There were also many who were not happy at the prospect of a German king and a Whig stranglehold on power.

In the North, key catholic Peers such as The Earl of Derwentwater, Lord Widderington and MPs such as Thomas Forster of Adderstone and Sir William Blackett of Wallington quickly fell under suspicion. On 22 September 1715 warrants were issued for their arrest. The young Earl decided a low profile would be advisable, hiding for two weeks in in tenants cottages and with friends and relations all across the area [6].

All would seem the actions of a man who dabbled in intrigue, but was not an instigator of rebellion. Nevertheless the Earl knew that he could not run and hide for ever, and after all, he had Stuart blood in his veins. Under the guise of a race meeting held at Wide Hough meadow near Dilston on 5 October 1715, the Earl and his compatriots decided to make their stand on the morrow. The next morning the Earl, his brother Charles and their small band set out to meet Thomas Forster, the commander of the Northumbrian Jacobites, and his men, at Greenriggs, a wild desolate moorland, between Redesmouth and Sweethope Lough. The die was cast.

The Rising in the North

The Northumbrian Jacobites of the ’15 have had a bad press, being described by one writer thus:

‘In October a handful of Catholic Gentry under Forster and Derwentwater, amateurs in rebellion and war, had ridden out in Northumberland [..]

The quixotic travesty of civil war by a mob of foxhunters, had found no support save from the more dare-devil of the Catholic gentry and Mackintosh’s Highlanders. The English Rebellion was at an end.’ [7]

The mission of the Northumbrian Jacobites was to capture Newcastle and thereby hobble the government in London by cutting off their coal supply. They would be supported by a French led invasion fleet which was expected to land on the Northumbrian coast. History however did not record this outcome. Instead, weak and indecisive leadership, lack of the promised support from the High Church Tories, inability to capture Newcastle and the failure of the French fleet to materialise left the Northumbrian Jacobites little choice but to head into the pro-Jacobite territory of Lancashire hoping for greater success.

Leo Gooch, however, has presented a more sympathetic and compelling view of the effectiveness of the Northumbrian Jacobites in his book ‘The Desperate Faction?’ He argues that the original plan formulated by the Earl of Mar, for a Northumbrian landing of the Jacobite forces, was militarily sound. It was only when this plan was shelved by Ormonde and Bolingbroke (without bothering to inform Tom Forster and the Northumbrians) in favour of a landing in the South West, that things started to go badly wrong. Gooch argues that when this new strategy failed, Forster was thrust into the role of commander of all the Jacobite forces in England. Although he and Derwentwater did their best, they were, quite literally fighting a losing battle [8].

Execution

That losing battle was at Preston. The supposed Jacobite support in Lancashire remained dormant and the rebel forces were defeated and their leaders captured and taken to London for trial. Many were condemned to die, some escaped, some were pardoned. Tom Forster who rode out with the Earl of Dertwentwater was executed but Derwentwater’s brother Charles managed to escape. The Earl himself, was lodged in the Tower of London, as befitted his status. His devoted wife Anna Maria stayed with him and petitioned for his release. It was not to be. He was beheaded on Tower Hill on 24 February 1716.

Catholic Martyr

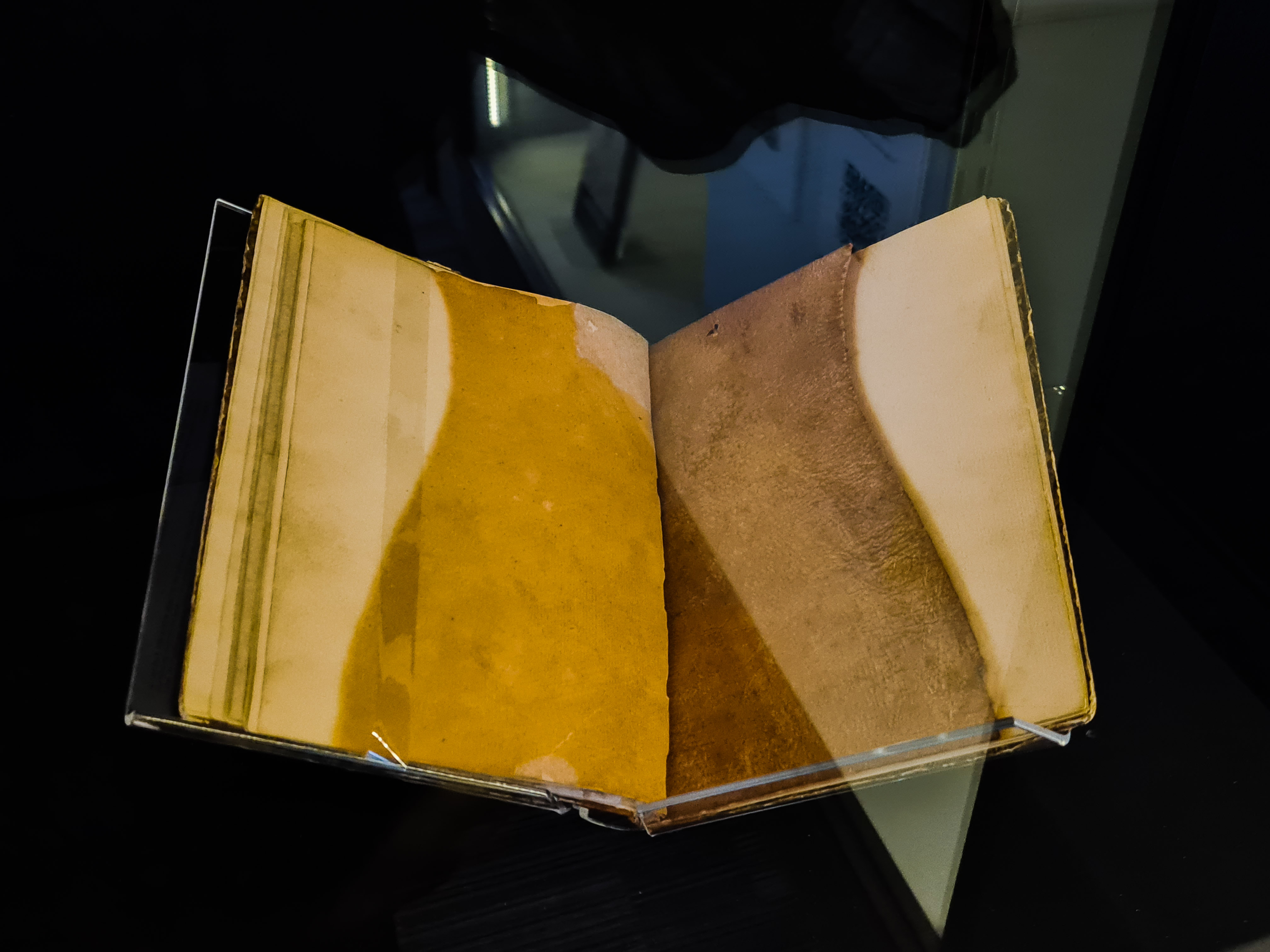

Once executed James’s body was wrapped in black cloth, with his severed head in red velvet. His body was then secretly conveyed to a surgeon called Metcalf who embalmed the corpse and removed the heart which was to be sent to the English nuns at Angers in France. Mr King the undertaker then provided a lead coffin covered in crimson velvet and gilt nails, to convey the third Earl back to his home at Dilston for burial in the chapel. It was said that his heart remained uncorrupted for many years and was able to heal those who touched it, it was especially effective on Scrofula or the king’s evil [9].

On his return to Dilston, the Northern Lights accompanied his procession. Many saw this as a sign of Heaven’s displeasure at the Earl’s execution, it was said the Devil Water ran red at Dilston. Already tales began to be told that would place James Radcliffe, the Jacobite third Earl of Dertwentwater firmly in the folk memory of the region.

James’s widow, Anna Maria, never returned to Dilston and died in Belgium 7 years later. The Radcliffe estates were confiscated by the government, but in a lengthy legal battle it was successfully argued that as James only had life interest in the Derwentwater estates and his son John should inherit the great wealth of the Radcliffes. Sadly though, he died in 1731 before reaching his majority. That left only Charles Radcliffe, James’s brother, as heir. Unfortunately he was was still under attainder for his part in the ’15 so could not inherit. By default then, the estates then passed back to the crown. The power of the Radcliffe’s was broken.

Whether James Radcliffe was a reluctant Rebel [10] or a passionate and committed Jacobite, his legend lives on in the North. Even today, Paranormal investigators such as Otherworld North East, and Christina Ogilvy and James Davidson, have reported strange anomalies in and Around Dilston Castle. Orbs, strange mists and dark figures still haunt the ruins of Dilston [11 & 12]. On a moonlit night it may still be possible to come across James and his young bride Anna Maria, walking by the Devil Water.

Access to castle:

http://www.northumbrianjacobites.org.uk/pages/detail_page.php?id=36§ion=27

Sources and notes

Dickinson, Frances, ‘The Reluctant Rebel A Northumbrian Legacy of Jacobite Times’ 1996, Cresset Books [1][3][5][6][10]

friendsofhistoricdilston.org/

ghostnortheast.co.uk/dilston.html

Gooch, Leo, ‘The Desperate Faction The Jacobites of North-East England 1688-1745’ 2001, Casdec Ltd [4][8]

Graham, Frank, ‘The Castles of Northumberland’ 1976 Frank Graham Books [7]

Liddell, Tony, ‘Otherworld North East Ghosts and Hauntings Explored’ 2004, Tyne Bridge Publishing [12]

http://www.northofthetyne.co.uk/Dilston.html

http://www.northumbrianjacobites.org.uk/pages/section_homepage.php?section=27

Matthews, Rupert, ‘Mysterious Northumberland’ 2009, Breedon Books [2]

Ogilvy, Christina and Davidson, James, A, ‘Haunting Dilston’ 2015, Powdene Publicity Ltd [9][11]

Leave a Reply