The Etiquette of Duelling

- No duels were to be fought on Sunday, on a day of a Festival, or near a place of public worship.

- A Principal was not to “wear light coloured clothing, ruffles, military decorations, or any other … attractive object, upon which the eye of his antagonist [could] … rest,” as it could affect the outcome of the duel.

- The time and place were to be as convenient as possible to surgical assistance and to the combatants.

- The parties were to salute each other upon meeting “offering this evidence of civilization.”

- No gentleman was allowed to wear spectacles unless they used them on public streets.

- There was to be at least 10 yards distance between the combatants.

- The Seconds were to present pistols to Principals and the pistols were not to be cocked before delivery.

- After each discharge the Seconds were to “mutually and zealously attempt a reconciliation.”

- No more than three exchanges of fire were allowed, as to exchange more shots was considered barbaric.

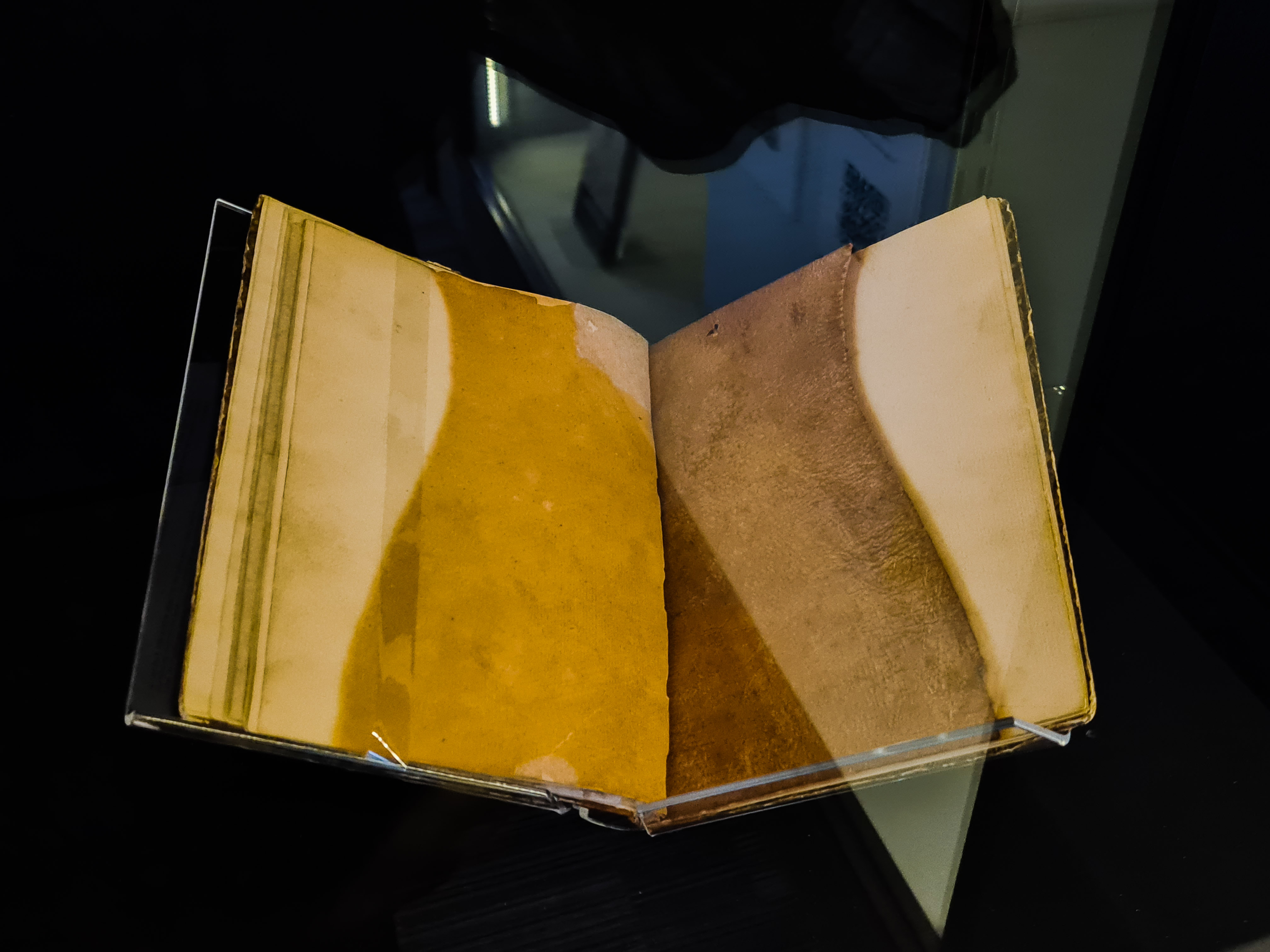

The above duelling rules were taken from the Royal Code of Honour which aimed to lay down a code of etiquette governing how duellists behaved[1]. During the height of duelling popularity a number of codes were written in Britain and in Europe, sometimes with conflicting rules and covering a range of topics including how to accept a challenge, how to behave after the duel and even how to die!

Despite slight differences expressed in the competing codes one area which they wholeheartedly agreed on was that honour of both the challenger and the defender must be maintained at all costs. This idea of personal honour goes to the heart of duelling and in turn acts as a mirror to the society in which duelling as a practice flourished. It also provides a thread connecting it to its distant medieval ancestors, trial by combat and the spectacle of the joust.

Duels were generally considered the preserve of men, in particular those from the aristocratic classes. To refuse a duel was viewed as a stain on a gentleman’s reputation. The most common reason to duel was over a perceived insult to a woman’s virtue but records show that on occasion women did take the initiative. In 1777 Paris, Mademoiselle Leverrier shot her former lover, Duprez in the face after he had left her for another woman. In fairness she had given him the chance to defend himself but chivalrously he had shot into the air, she had no such qualms[2].

The Honour of the Hotots

Another famous duel involving a woman reaches back in time to a period of history when jousts were not only a popular form of entertainment but also a pretty useful way of settling scores.

In 1390 a duel took place in Northamptonshire, on the line was family honour. The story believed to have been documented by a monk living in Clapton during the reign of Henry VII, tells of Sir John Hotot, a wealthy landowner who was in dispute with a man called Ringsdale over the title to a piece of land. Eventually the situation escalated to the point where the only way to resolve their quarrel was through a contest of skill and strength. Unfortunately when the appointed day came, Sir John was taken ill, suffering from gout and so his daughter and heiress Agnes “rather than he should lose the land, or suffer in his honor”[3] decided to take her father’s place.

Dressed in armour “cap-a-pie” style[4], armed with a lance and astride her father’s steed, she set out to meet Ringsdale. She was said to have fought bravely and hard and finally managed to dismount her opponent. Once on the ground she removed her helmet and with her hair cascading down her shoulders revealed herself to a stunned Ringsdale. Another variation is that she also removed her breastplate in order to remove any doubts that the victor was in fact a woman. This action despite adding a dramatic flourish to the story is extremely unlikely, nothing to do with modesty but simply due to the difficulty of removing a breastplate from armour!

The Crest of the Dudleys of Clapton

Having saved the reputation of her family, Agnes later married into the wealthy Dudleys’ of Clapton or Clopton, Northamptonshire. In honour of Agnes’ courage, her in-laws designed a new crest, depicting the bust of a woman with dishevelled hair, a bare bosom and a helmet on her head with “the stays or throat latch down”[5]. The crest was rumoured to have survived for as long as the male line of the Dudley family held the lands of Clapton. In 1764, Sir William Dudley, the last male descendant of the Clapton Dudleys died.

Agnes and Skulking Dudley

This intriguing tale of honour and daring has over time become conflated with the darker legend of ‘Skulking Dudley’. In this version, Agnes is the daughter of Dudley, the bullying lord of Clapton Manor. Her father having insulted a number of his fellow landowners in the area was finally challenged to a duel by Richard Hazelbere of Barnwell. By nature a coward Dudley feigned illness, took to his bed in order to avoid having to fight and persuaded or forced his daughter to go instead. According to this account, Agnes despite fighting valiantly, loses. Just before striking the fatal blow, Hazelbere discovers her identity and allows her to live. Impressed by her courage and virtue, they marry shortly afterwards. Dudley finally gets his just deserts when he is decapitated by Hazelbere.

The Legend of Skulking Dudley

The actual legend surrounding ‘Skulking Dudley’ is much more unpleasant and has absolutely nothing to do with Agnes.

The most popular version is that Dudley, a member of the influential Dudleys of Clapton was known to be a violent and vicious character, bullying his servants and tenants. In 1349 he was believed to have committed a gruesome murder. Who he was supposed to have murdered is unclear but one account claims that it was in fact, Richard Hazelbere. Dudley was reported to have shown no remorse and instead revelled in the deed[6]. The tables turned when Dudley was killed by a scythe to the head when a harvester he was whipping fought back in self-defence[7].

For some reason at the beginning of the last century after an absence of nearly 600 years his ghost minus a head suddenly reappeared to torment the villagers (maybe for imagined slights inflicted on him by their ancestors). Locals reported having seen him make his way from the site of Clapton Manor, past the old graveyard, along Lilford Road to a small coppice (later named after him). His spirit was named ‘skulking’ from its habit of dodging in and out of hedgerows[8]. His soul was finally laid to rest by the efforts of Bishop of Peterborough aided by twenty-one clergymen. Skulking Dudley has not been seen since. A popular local tradition has it that Dudley was hunch-backed[9], a physical deformity which was in the past often viewed as the outward symptom of a corrupt and vicious nature – just think of the much maligned Richard III.

One other interesting variation of the Skulking Dudley legend manages to bring it back to the concept of a duel. In this description, Dudley killed his own cousin in a duel over the ownership of Clapton Manor House. Despite not being injured in any way, Dudley suddenly aged and withered, dying soon after[10].

Women who joust

How probable is the story of Agnes Hotot? In 1348 a British chronicler records how at tournaments beautiful ladies from wealthy families and of noble lineage would regularly take part in jousting competitions. At one event he recounts that as many as forty female contestants were seen participating. From his writing, it becomes clear that he holds these women in low esteem as he describes how dressed in divided tunics with hoods, wearing knives and daggers they fought on splendidly dressed horses and “in such a manner they spent and wasted their riches and injured their bodies with abuses with ludicrous wantoness”[11]. Whether or not the chronicler’s disparaging remarks reflect how the medieval world in general really felt about female jousters is unclear but accounts of women fighting in tournaments do continue to appear in later centuries. So the evidence indicates that the legend of Agnes Hotot could very well be rooted in a real event, as to the legend of Skulking Dudley that could be stretching possibility a little too far!

Bibliography

Pistol Dueling, Its Etiquette and Rules, Geri Walton, https://www.geriwalton.com/pistol-dueling-its-etiquette-and-rules/, 2014

Duel: A true story of death and honour, James Landale, 2005

Haunting History of Clopton, facebook.com/historyhaunted/videos/1824694297556642

Agnes Hotot, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agnes_Hotot

The Encyclopaedia of Amazons, women warriors from Antiquity to the Modern Age, Jessica Salmonson, 1991

Dudley, Sir Matthew, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1690-1715/member/dudley-sir-matthew-1661-1721

Dudley baronets, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dudley_baronets

Skulking in the Woods, northamptonchron.co.uk/news/opinion/skulking-in-the-woods-1-4402161

Haunted England: The penguin book of ghosts, Jennifer Westwood and Jacqueline Simpson, 2010

A genealogical and heraldic history of the extinct and dormant baronetcies of England, John Burke, 1838

Notes

[1] Pistol Dueling, Its Etiquette and Rules, https://www.geriwalton.com/pistol-dueling-its-etiquette-and-rules/

[2] Duel: A true story of death and honour, James Landale, 2005

[3] Agnes Hotot, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agnes_Hotot

[4] Duel: A true story of death and honour, James Landale, 2005

[5] Ibid

[6] Skulking in the Woods, northamptonchron.co.uk/news/opinion/skulking-in-the-woods-1-4402161

[7] Ghostly Tales of the Unexpected, northantstelegraph.co.uk/news/ghostly-tales-of-the-unexpected-1-718777

[8] Haunting History of Clopton, facebook.com/historyhaunted/videos/1824694297556642

[9] ibid

[10] Ghostly Tales of the Unexpected, hnorthantstelegraph.co.uk/news/ghostly-tales-of-the-unexpected-1-718777

[11] The Encyclopaedia of Amazons, women warriors from Antiquity to the Modern Age, Jessica Salmonson, 1991

All links were correct when the article was published.

Leave a Reply