Dr Croghan and the Coughing Cave People

In the state of Kentucky, beneath a national park, you will find the longest known cave system in the world. Mammoth Cave lives up to its name, comprising more that 630km (400 miles) of known passageways, but it is not the geology which is the subject of this blog. It is a story so dark and extraordinary that it has inspired visitors to believe that even now, they still hear spectral coughing in the endless caverns.

In 1842, a Kentucky doctor lead a group of volunteers to live deep within the bowels of the cave, in the pitch-darkness, for months on end. Who was Dr John Croghan? And why did he believe that leading 15 patients into the unique conditions of Mammoth Cave may be the key to treating tuberculosis?

Tuberculosis

In the nineteenth century, Tuberculosis was an un-treatable condition. Germ theory was not yet dominant in understanding the cause of disease, and a working antibiotic would not be developed for more than 100 years, meaning that this mysterious illness was most often a death sentence. Known variably as Consumption, Pthisis, Scrofula, and the White Plague, Tuberculosis is a bacterial disease which most commonly affects the respiratory system. Those who did survive would frequently suffer with flare-ups and respiratory difficulties for the rest of their lives.

The most common lay term for Tuberculosis was Consumption, referring to the wasting effects of the disease. This rapid weight loss, pale skin, and fever lead to a gaunt and spectral appearance and extreme fatigue. Much has been made in historiography and popular culture of the ways in which Tuberculosis was portrayed at the time as a ‘romantic disease’, revealing the sensibility of the sufferer, and leading to the creation of some of the world’s greatest art and literature. So influential was this romanticization of tuberculosis that it became fashionable for both women and men to be waif-thin, emphasize their collarbones, and powder their faces to appear as pale and feverish as possible.

Late-stage tuberculosis is nonetheless extremely uncomfortable for those infected and, despite this morbid link between beauty, genius, and death in the wealthier sections of society, tuberculosis did not discriminate based on class and was an epidemic of biblical proportions amongst the lower classes in urban areas.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, a great deal of effort and resource was being invested by the learned men and philanthropists of the age to find a cure and a means to prevent transmission. Though medical professionals disagreed about the cause of the disease, many understood it to be contagious and public health campaigns often encouraged quarantine (a next to impossible feat in the cramped and squalid conditions in which poor and working-class individuals lived and worked). Meanwhile, charitable organisations funded sanatoriums to separate sufferers from the general populous, and learned men continued to argue and debate over their observations and experimental treatments.

Unfortunately, their valiant efforts were limited by contemporary understanding of what diseases were and how they were transmitted. Whilst Galenic medicine and the notion that diseases were caused by an imbalance in the four humours continued a significant decline as a prevalent way of understanding the body and diagnosing patients throughout the nineteenth century, treatments for diseases did not keep pace with the new discoveries of anatomy and pathology. For this reason, despite the improvements in observation and diagnosis, the treatment for many diseases by even the most preeminent doctors continued in the tradition of focusing on emetics, bleeding, and regimen. The term ‘regimen’ refers to a prescribed daily routine based the idea that certain food, drinks, locations, and temperatures may have an impact on the health of patients. However, the prevailing, and best available treatment for tuberculosis in the early and mid-nineteenth century was bed rest, short walks, and fresh air.

Dr John Croghan and the Mammoth Cave

John Croghan of Louisville, Kentucky was a doctor from a wealthy local family, searching for a treatment for tuberculosis. Having worked as a founder and director of the Louisville Marine Hospital from 1823 to 1832, he was himself diagnosed with Tuberculosis. In 1839, Croghan purchased 2,000 acres of land, including Mammoth Cave, and several enslaved individuals for $10,000. Part of his intention was to profit from the tours of the cave, which had been started in 1816. However, Croghan also had another motive…

His plan was to open a large health resort deep within the cave system. The foundation of his experimental treatment was to use the temperate climate of the cave, and its presumed stabilizing effect on the body to potentially temper or cure tuberculosis. Croghan noted the steady temperature of the cave and believed the air to have curative properties, observing that other organic matter did not appear to wither or decay in the cave. Croghan confirmed 11 tuberculosis patients, four companions, and the child of a patient to live in the cave over the winter of 1842.

The logic of the assumption that the conditions in the cave may improve their condition rested in the humoral tradition, whereby respiratory issues were usually attributed to an excess of phlegm; an imbalance of coldness and wetness. Therefore, the appropriate treatment to correct this imbalance was to maintain a consistent, temperate environment, devoid of changes and extremes, as could be experienced in Mammoth Cave. (This may seem an odd logic but to this day, you may still receive advice that exposure to intemperate climates and wetness may induce illness, despite nigh on a century of evidence that colds are caused by viruses. Thus, still why we refer to rhinoviruses as the common ‘cold’.)

The characteristics of the cave which Dr Croghan chose seemed ideal for his purpose. In the winter of 1842, Dr Croghan led his patients down into the caves where they, as far as we know, willingly engaged in his experiment. They were to live in the cave indefinitely, or until they were well enough to leave. The residents of the cave had little access to anything beyond the meals delivered to them by enslaved people. Photographs show individuals standing and sitting on simple stone and wooden huts, some of which are still standing to this day in the belly of the cave.

For five months, Dr Croghan’s patients lived as a commune in the depths of the limestone caves. Their only light came from lard-oil lamps and simple fires, with the constant belch of smoke and fumes filling chambers and lungs with noxious gases. They read episcopal sermons and ate wholesome food, delivered by the enslaved persons who lived outside the cave formation.

A server named Alfred noted, “I used to stand on that rock and blow the horn to call them to dinner. There were fifteen of them and they looked more like a company of skeletons than anything else.”

All the while the experiment ensued, tourists were still being guided throughout the cave system. Both servers and tourists alike spoke of the eerie sight of pale, spectres emerging from shadow, smoke, and flame, hacking and coughing in the muted torchlight.

They encountered “a bizarre scene. Pale, spectral figures in dressing-gowns moved weakly along the passageway, slipping in and out of shadowed huts, the silence of the cave broken by hollow coughing and muttered conversations.”

The results of this experiment, to the modern observer, would appear almost inevitable. Of the fifteen people who descended into the Mammoth Caves, five died before the experiment was unceremoniously ended. Their bodies were laid out on a stone now known as ‘Corpse Rock’. Whether the time which the remaining participants spent in the cave had any bearing whatsoever on their lifespan is impossible to say now in any certainty. However, with the benefit of modern medicine it is reasonable to state that confining tuberculosis patients together in damp, dark environments brimming with toxic smoke pollution is unlikely to have had any sort of positive effect on their vitality. Dr Croghan himself passed away as a result of Tuberculosis in 1849.

Legacy

The unequivocal failure of Dr Croghan’s experiment was commonly discussed in the popular press, but the story seemed only to gain more traction as the American middle-classes gained more disposable income, and tourism became a common all-American pass-time. A very famous and entertaining spooky story has always been a very good selling point when advertising a tour… Just ask the tour guides of Whitechapel. Remarkably, the industry around these tours in the late nineteenth century became so acrimonious that it led to the wonderfully named ‘Kentucky Cave Wars’, where rival land-owners would sabotage signs and spread misinformation about Mammoth Cave in order to deceive the public to coming to their own private cave tours. Like an episode of Wacky Races.

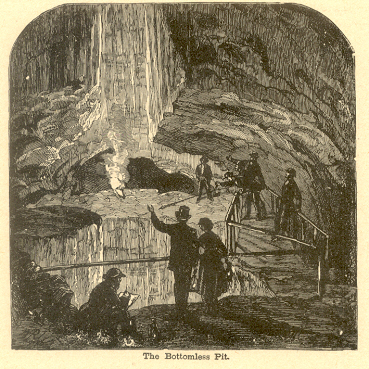

By the late nineteenth century, Mammoth Cave was an internationally noteworthy natural curiosity and was the subject of a number of short stories and periodicals. In 1877, 35 years after the beginning of the experiment in Mammoth Cave, Harper’s Weekly published an article which included two engravings, documenting and dramatizing the morbid history of the cave. With a circulation in excess of 100,000, Harper’s Weekly was a very successful and ubiquitous publication in the USA. The inclusion of such an article suggests that there was still significant interest in the story of Dr Croghan and his patients long after their demise. In fact, the first line of the page reads “The Mammoth Cave of Kentucky has been so frequently described both in our own and other periodicals that the two engravings on this page will need but a brief mention.”

The engravings are accompanied by the following, very short description:

“[The first image] represents the ruins of a hotel which was built in one of the larger chambers of the caves for the accommodation of consumptive and asthmatic patients, the equable temperature and nitrous atmosphere having been recommended as a remedy for diseases of the lungs. It has been long abandoned, however, invalids having found little to no alleviation for their sufferings, whatever benefit may have been derived from the peculiar air having been more than counterbalanced by the depressing influences of a sojourn under-ground/ the second sketch shows a party crossing the cave river, which has received the somber[sic] name of the Styx.”

Named for the mythological Greek river which marked the boundary of the lands of the living and the dead, it is possible that the macabre history of the cave also wound its way into the naming of landmarks and features.

H.P. Lovecraft

H.P. Lovecraft was an American writer, famed for his horror and science fiction.

In 1905, Lovecraft published a short story about a man lost in Mammoth Cave who comes across an anthropomorphic beast in the darkness. He writes:

“The creature was described as having snow-white hair, rat-like claws on its hands and feet with pale, white skin. Its eyes were black, lacking irises and sunken into its skull. Finally, it was very gaunt.”

In the story, Lovecraft mentions that a colony of consumptives lived in the cave in a gigantic grotto.

Knowing what we do about the physical symptoms of tuberculosis, and the infamy which of the story of Dr Croghan and the consumptives maintained in the popular psyche, it appears that the beast in the cave is heavily inspired by the stories of those tourists who claim to have seen patients shuffling about the cave in their dressing gowns, looking pale, gaunt, and one step from death.

Modern TB

In 1882, more than 40 years after Dr Croghan’s experiments, Dr Robert Koch isolated the cause of Tuberculosis: Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. This discovery was the first step on our continuing journey to finally understand, control, and treat Tuberculosis; from the development of the BCG vaccine in 1921 and the discovery of the antibiotic Streoptomycin in 1943, to the four drug cocktail which was discovered in 1966 and is still widely used in treatment today. Contemporary scientists continue to work tirelessly, pushing on in leaps and bounds to imagine new, innovative ways to improve the health of people all over the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) have an ambitious target to eradicate Tuberculosis by 2030.

However, as concerns rise about increasing incidences in the UK, multi-drug resistance, and how to combat the socio-economic inequality which continues to stifle our ability to manage pandemic and endemic diseases, one has to wonder; have they tried Mammoth Caves?

Leave a Reply