by Joseph Jacobs 1894– Illustrated by John D. Batten

‘Whisht! Lads, haad yor gobs,

An Aa’ll tell ye’s aall an aaful story

Whisht! Lads, haad yor gobs,

An’ Aa’ll tell ye ‘boot the worm 1

Anyone who went to school in the North East of England will probably be familiar with the famous chorus from the folk-song The Lambton Worm. The song was written in 1867 by C M Leumane and quickly took on a life of its own in popular culture. My own memories of learning it as an eight-year-old, were that I loved the catchy chorus, but there were way too many verses to memorise!

Tales of worms or dragons are not uncommon in British folklore, one only has to think of St George and the Dragon to appreciate how entwined dragon-slayers are in national and regional identity.

But is the tale of the Lambton Worm simply another Dragon Slaying tale, or is there more to it than that?

The Legend of the Lambton Worm

The Legend of the Lambton Worm first appeared in print in 1785. Antiquarian William Hutchinson outlined the folk explanations of the formation of Worm Hill, a glacial moraine, in Fatfield, Washington:

“Near this place is an eminence called the Worm Hill, which tradition says once possessed by an enormous serpent, that wound its horrid body round the base; that it destroyed much provision, and used to infest the Lambton estate, till some hero in that family engaged it, cased in armour set with razors…the whole miraculous tale has no other evidence than the memories of old women…” 2

This figure from the distant past was often identified as Sir John Lambton, Knight of Rhodes.3

However, these written accounts draw on older local oral traditions.

Here is my summary of the Legend of the Lambton Worm, as we know it today:

Young Lambton, the heir to the Lambton Estate, was fishing in the River Wear one Sunday, when he should have been in church, when he caught a very strange eel-like creature with a dragons head. Unhappy with his scrawny catch, he blithely discarded it down a well, later known as Worm Well, and went on his merry way. Young Lambton grew to repent of his profane ways, and joined a crusade, leaving his home for many years. The worm, however, did not leave, and was thriving and growing to a prodigious size at the bottom of the well where it was discarded. So much so, that it had to relocate to a larger habitat, choosing first to wrap itself around a local hill, which became known as Worm Hill, and later favouring a rock in the River Wear.

All would have been well enough, had the worm not also had a very large appetite. Cattle, Sheep, and even the occasional child all made it onto the worm’s menu. Consequently, the locals lived in terror of the poisonous and very hungry worm that young Lambton had unwittingly set loose amongst them. Finally, young Lambton returned, a new man, from the crusades and set about righting the wrong he had set in motion in his youth. His initial skirmishes with the worm were unsuccessful until he consulted with a local witch or wise woman.

The wise woman gave him some sage advice on how to tackle the slippery beast, which asides from being extremely dangerous, had a habit of being able to pull itself back together if it was ever cut in half. Following her advice almost to the letter (this will be important later) he donned a suite of armour studded with razors and took on the worm on its home territory, the River Wear. The worm, seeing Lambton as another tasty snack, wrapped itself round the knight, in order to crush him, but was instead sliced and diced, with all of its pieces flowing away in the river, never to reform again. The Worm was dead, and the local people were saved and there was much rejoicing!

All would have been well and good, except for one small omission by Lambton, the witch had warned him that once his mission was accomplished, he must kill the first thing that greeted him on his return home, or else the next nine generations of Lambton chiefs would not die in their beds. Despite taking some precautions, Lambton’s father was the first to greet him on his return, and well, young John couldn’t bring himself to kill his own father, so the curse fell upon the Lambton’s and the next nine generations did not die in their beds.

Dragon Tales

Tales of Dragon Slayers are common throughout Medieval Britain and Europe. The Northeast of England (taking in Northumberland, County Durham and Yorkshire) has twenty or so tales of Dragons and their slayers, for example, the Sockburn Worm and The Laidly Worm to name but two.4

What has been noted to be different about English, and these Northern tales, is that, unlike many of the European tales, the hero is not seeking to win treasure or maiden fair, but has a more pragmatic aim, often to save the local area from some peril (as in the Sockburn and Lambton stories). 5,6

What is particularly distinctive about the Legend of the Lambton Worm, is that once the hero has slayed the dragon, he does not win maiden fair or treasure, in fact he and his family are cursed for several generations to come.

Unpacking the Worm

There are certain elements in the Lambton Worm tale that are worth unpacking.

Dragons and Worms (terms often used interchangeably in historic texts) can mean different things in different cultures and depending on who is using them (see Miss Jessel’s excellent post for more on Dragons in general). For the Medieval church, dragons often represented evil, but for many noble families they represented valour in fighting, so appear on many family crests.7 They have also been linked to natural and manmade catastrophes, water spirits, and remnants of ancient nature religions (of which more below).

Monster theory

Jeffrey Jerome in Monster Culture considers the monster to be a cultural body. The device of the monster can be used to present a warning (of lines not to be crossed), to reveal a truth, to represent the ‘other’ (both within society or external to it), or to embody a cultural moment (often a moment of change). In killing the monster, the hero reaffirms group identity and order. And of course, as any horror fan will know, even if you kill the monster, it may still return.8

The Legend of the Lambton Worm can be seen to contain many of these attributes.

Toxic Masculinity

In folklore, fishing on a Sunday can be seen as shorthand for profane behaviour, young Sir John should be in church attending to his Christian duty. One interpretation of the legend, suggested by Tom Murray and discussed in his interview with James Tehrani, an anthropological folklorist, is that the worm as a metaphor for toxic masculinity. It is Sir John’s own out of control behaviour that has put the community in danger, and only Sir John can defeat it, by reforming himself through Christian duty (going on a crusade) then defeating the very phallic worm on his return.9

This idea of toxic masculinity has something of a pedigree, in 1823, William Hutchinson suggested that worm tales, such as the Lambton Worm, could represent a folk memory of the disastrous Viking raids on the Northeast coast that took place in the eighth and nineth centuries. It could perhaps commemorate a local hero who protected his community from them, or more broadly, show the community dealing with the threat itself, without outside assistance. 10

Water beings and the old religion

Another interesting interpretation of the Lambton Worm is that the worm is a metaphor for the relationship between man and water, and that this is part of a global tradition. Veronica Strang11 sees the popularity of dragons in the Medieval period as linked to the changing relationship with water and nature, new technologies and new social and political organisation both controlled water (e.g., through irrigation) also commodified it.

The Lambton worm is set in the Medieval period, at this time Church felt it was facing an existential threat on two fronts: externally in the form of the Islamic world, and internally from lingering nature worship amongst supposedly Christain communities (evident in the churches concerted effort to rededicate pagan holy wells to Christian saints).

Strang projects that the tale of the Lambton Worm could be read as the story of a local lord who fails in his Christian duty, allows pagan nature worship to flourish in his community, and, metaphorically, poison the well. Only when he has taken up his Christian duty and defeated another set of ‘pagans’ by joining the crusade against Islam, can he return home and re-assert Christianity in his local community. Here then, the worm represents the ‘other’ or pagan, which must be defeated in order to restore the established order. [strang] This potentially also links into the worm’s ability to come back to life, until the wise woman offers her advice to Lambton on how to vanquish it for good, if there was a fear that old nature religion would keep on resurfacing if left unchecked.12

A Local tales for local people

Another important factor in the Legend of the Lambton Worm is that it provides a heroic and ancient pedigree for a prominent local family, the Lambton’s, setting up one of their ancestors as the hero of the hour, protecting his community. It also incorporates tangible local landmarks – Worm Hill in Fatfield, Washington – further fixing the legend to the local imagination.

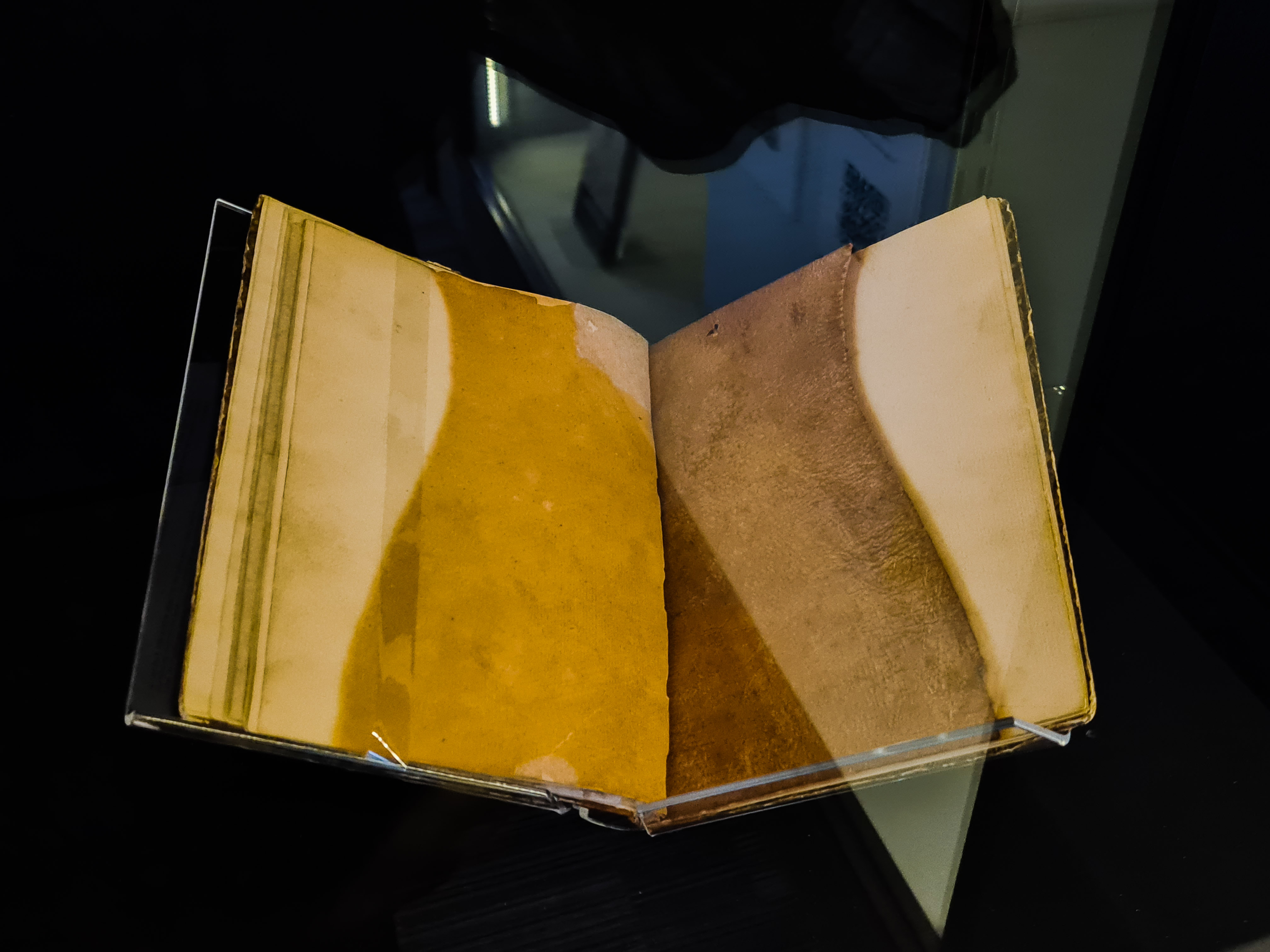

Jamie Beckett13 has identified the Legend of the Sockburn Worm as a potential inspiration for the Lambton Worm. The Sockburn Worm is attached to the ancient and once powerful Coyners’ family and is a much older tale but running along similar lines. Sir John Conyer’s defeats the dragon and saves the day with his trusty falchion sword. Visible reminders of Conyers bravery and chivalric pedigree remained for all to see in the ‘greystone’ marking the worm’s burial place and the Conyers’ Falchion, still extant today and held in the Treasury at Durham Cathedral (it forms part of the ceremony of enthroning new Bishop’s of Durham to this day).

Beckett sees the rise of the Legend of the Lambton Worm growing out of this tale, and coinciding with the declining fortunes of the Conyers family in the seventeenth century, and the rise of the ancient but not previously powerful Lambton’s from that period onwards. 14

The Lambton Worm and the Radical Politician

Folktales and legends morph and change over time. The Legend of the Lambton Worm is no different. One element of the tale that I certainly grew up believing, was that the Worm wound its tale around Penshaw’s Monument. I’d never heard of Worm Hill or Fatfield. So why is Penshaw’s Monument (or Penshaw’s Folly) come to be intrinsically linked to the Legend of the Lambton Worm?

The simple answer is that in 1867 C.M. Leumane wrote a very catchy tune about the Lambton Worm, forever linking it with Penshaw:

This feorful woorm wad often feed

On calves an’ lambs an’ sheep,

An’ swally little bairns alive

When they laid doon to sleep.

An’ when he’d eaten aal he cud

An’ he had has he’s fill,

Away he went an’ lapped his tail

Ten times roond Pensher Hill. [Cj]

The Penshaw Monument, visible for miles around, is a Greek Temple on a hill in Penshaw Village Co Durham. It was built by public subscription in 1844/5 in honour of John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, who died a few years earlier in 1840.

John Lambton was born in 1792, he was Byronically handsome, rebellious, and had suffered many tragedies in his life (his first wife, Harriet, who he married for love, in 1812, died only three years later, they had three children who all pre-deceased him). While he was undoubtedly a tragic and romantic figure, what endeared him to the local population was his politics.

Known as Radical Jack, he was MP for Co Durham from 1812, pursuing radical Whig politics, he was in favour of a number of very progressive reforms such as secret ballots, fixed term parliaments, universal suffrage. Following the shocking Peterloo Massacre in 1819, where a large crowd of unarmed people, campaigning for parliamentary reform, were violently attacked by the cavalry, resulting in many deaths and injuries, Lambton controversially criticised the actions of the establishment in attacking and killing innocent people. He was later instrumental in the passing of the 1832 Reform Bill. All of this made him terrifying to the establishment and beloved of the working classes.

Such was his reputation, that by the 1820’s and 30’s at least three chapbooks existed that told the tale of the Lambton Worm, with the inferred compassion between the contemporary John Lambton defending the poor from political and social oppression, and his Romantic and heroic namesake ancestor, protecting the poor from a dangerous worm, in the distant chivalric past.15

Such was his popular appeal, that a lasting monument, funded by public subscription, was erected in his honour on Penshaw Hill. Tens of thousands of spectators watched as it’s foundation stone was laid in a Masonic Ceremony by the 2nd Earl of Zetland.16

In conclusion

I am drawn to Veronica Strang’s interpretation of the Worm as a metaphor for the church suppressing lingering elements of nature religion in its congregation, whilst fighting off ‘pagan’s abroad. This would seem a good fit if the legend was of Medieval or earlier origin. However, if the tale was created later, then Jamie Beckett’s view that these type of Legends were used by prominent families to establish their pedigree in the dim and distant past, then the legend of the Worm might be best interpreted as a public relations exercise by a family on the rise.

Perhaps more likely, is that it may contains elements both these theories, and others, with the most recent and most popular written iterations of the legend, from 1785 and onwards, being designed to give prominence to the powerful Lambtons, and to handsome, radical, John 1st Earl Lambton, in a fashionably Romantic and nostalgic way.

Perhaps it is appropriate that the worm is still slippery enough to both elude and fascinates us today, like all good folktales, it is alive and well and no doubt, continuing to evolve through the ages with each retelling.

There is undoubtably a lot more that could be said about the Legend of the Lambton Worm, its origin (ancient or otherwise), and its deeper meanings. For anyone interested in finding out more about the Lambton Worm (and other worms, dragons, and water spirits), I have provided a list of excellent sources below.

You can hear Lenora talking about the Lambton Worm on the Voices from the North East Halloween Special podcast, here:

You can hear The Lambton Worm (C.M. Leumane, 1867) arranged and performed by Geordie Wilson on YouTube, via the link below.

Notes

- The Lambton Worm composed in 1867 by C. M. Leumane

- Jamie Beckett, The History of the Lambton Worm and Sockburn Worm

- Robert Surtees et al, The history and antiquities of the county palatine of Durham 1816-40

- Jamie Beckett, The History of the Lambton Worm and Sockburn Worm

- Icy Sedgwick, The Lambton Worm and Penshaw Monument

- Jacqueline Simpson and Jennifer Westwood, The Lore of the Land

- Icy Sedgwick, The Lambton Worm and Penshaw Monument

- Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Monster Culture

- Tom Murray, Tracing the Cultural History of the Monstrous Lambton Worm

- Veronica Strang, Reflecting nature: water beings in history

- ibid

- ibid

- Jamie Beckett, The History of the Lambton Worm and Sockburn Worm

- ibid

- ibid

Sources

Beckett, Jamie, The History of the Lambton Worm and Sockburn Worm The History of the Lambton Worm and Sockburn Worm – (durham.ac.uk)

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome, Ed., 1996, Monster Theory: Reading Culture [chapter 1 Monster Culture]

Leumane, CJ, 1867, The Ballad of the Lambton Worm, available at: https://wp.sunderland.ac.uk/seagullcity/the-ballad-of-the-lambton-worm/

Murray, T, 2016, Tracing the Cultural History of the Monstrous Lambton Worm, https://www.modernaustralian.com/news/2237-tracing-the-cultural-history-of-the-monstrous-lambton-worm

Sedgwick, Icy, The Lambton Worm and Penshaw Monument, https://www.icysedgwick.com/lambton-worm/ 13 July 2017

Simpson, Jacqueline, Westwood, Jennifer, 2006, The Lore of the Land: A Guide to England’s Legends, from Spring-heeled Jack to the Witches of Warboys

Strang, Veronica, 2015, Reflecting nature: water beings in history in Waterworlds : anthropology in fluid environments. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 247-278. Ethnography, theory, experiment. (3).

Surtees, Robert, Taylor, George, Raine, James, pre-1850, The history and antiquities of the county palatine of Durham 1816-40

Leave a Reply