Join us at the Haunted Palace Blog as we investigate the Rat in the Skull.

In 1789, Bishop Shute Barrington authorised the remodelling and reordering of Salisbury Cathedral[1]. The man he hired for the job was the famous architect and rival of Robert Adam, James Wyatt. As part of the plan, Wyatt oversaw the repositioning of the Cathedral’s tombs, from different parts of the Cathedral into the nave. One of the tombs, that of William Longespée (which had been originally placed in the Trinity Chapel, the chapel being at the time of his death the only part of the cathedral to have been completed) was opened. Why Wyatt decided to open up Longespée’s tomb is not known, it could have made it easier to move or it might have just been out of sheer curiosity. Whatever the reason, the tomb was discovered to contain a rather surprising guest – the well-preserved skeleton of a black rat, positioned in of all places inside Longespée’s skull! To add to the mystery of how the rat got into the tomb in the first place was the fact that on testing, traces of arsenic were found in its body. So, what terrible secret did the rat reveal, was Longespée murdered or was there a more innocent explanation and is it possible that we will ever know the truth?

PART 1: Who was William Longespée?

Born around 1176, William Longespée was the illegitimate son of Henry II. For a long time, his mother was believed to have been Rosamond with whom Henry had an infamous affair. It was only with the discovery of documents in the twenty-first century that it was revealed that his mother was in fact, Countess Ida de Tosny, later the wife of Roger Bigod, 2nd Earl of Norfolk[2].

William gained his nickname ‘Longespée’ from his great physical size and his use of oversized weapons. He was acknowledged by Henry and given the honour of Appleby in Lincolnshire in 1188[3] and the right to use the coat of arms of his grandfather, Geoffrey of Anjou[4]. In 1196, Richard gave William permission to marry the immensely wealthy and sought-after heiress, Ela of Salisbury, 3rd Countess of Salisbury and granted him the title and lands of the earldom. William and Ela had six daughters and four sons.

William was raised with his half-brothers and although he chose to fight alongside Richard I in Normandy, it seems that his loyalty lay with John. William was one of the few people that John trusted and William served him well as both a diplomat and a commander. There was only a brief period of time when William’s faith in John was tested which was in the Baron Wars when John fled to Winchester on the arrival of Louis of France on English soil. Maybe William did for a short time believe that John had lost or perhaps he was disgusted with John’s cowardly behaviour[5], it is hard to tell. Suffice it to say, William returned to John’s side, eventually pledging his loyalty to John’s son, Henry III. William along with William Marshal fought to establish the young king in his rightful place. Longespée also played his part in bringing the siege of Lincoln to a satisfactory conclusion and was granted the title of Sheriff of Lincolnshire and given the role of castellan of Lincoln Castle. This honour led him to a bitter enmity with the previous castellan, the shrewd and indomitable Nicholaa de la Haye Nicholaa de la Haye: The female sheriff of Lincolnshire [6].

Over his lifetime, Longespée held a number of important positions including the High Sheriff of Wiltshire, Lieutenant of Gascony, Constable of Dover, Lord Warden of the Ports of Cinque, Warden of the Welsh Marches and Sheriff of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire[7]. An outstanding and fearless soldier, Longespée took part in many conflicts but he will always be known for one in particular, which is the Battle of Damme.

The Battle of Damme

The Battle of Damme occurred during the 1213-1214 Anglo-French War. On the 30/31 May 1213, Longespée commanding the English forces (comprised of 500 ships) accidentally came across a large French fleet under the supervision of Savari de Máuléon[8] in the vicinity of the port of Damme in Flanders, whilst most of the French crew were ashore pillaging the surrounding villages and countryside. Encountering limited resistance, Longespée captured the 300 French ships at anchor and looted and fired at a further 100 beached ships. Phillip II, who was at this time besieging the city of Ghent as part of his strategy for the suppression of Flanders, on hearing the news immediately marched back to Damme[9]. Phillip managed to drive off the English landing forces but decided that to be on the safe side it was advisable to burn the remainder of his fleet to prevent them from falling into English hands. Longespée’s actions put an end, for the time being, to any designs the French might have had on England. It was also extremely lucrative “Never had so much treasure come into England since the days of King Arthur”[10]. The Battle of Damme earned its place in the history books as the first great English naval victory.

The End of the Road

Longespée had an eventful life. He had survived wars, civil unrest, his brother King John’s notoriously capricious nature and being held for ransom. In 1224, Longespée left England for Gascony to help protect England’s interests in the region. On the return journey in 1225, a violent storm blew up and Longespée’s ship was nearly lost. Shipwrecked, he managed to make his way to the monastery on the Île de Ré where he took refuge[11]. He remained there for a few months until he was able to return to England. Longespée died at Salisbury Castle, not long after his return.

Longespée was buried at Salisbury Cathedral in 1226, the first person to ever be buried at the cathedral[12]. The cathedral must have held an important place in his heart. Both he and Ela had taken a strong personal interest in the new building, laying down foundation stones in 1220[13].

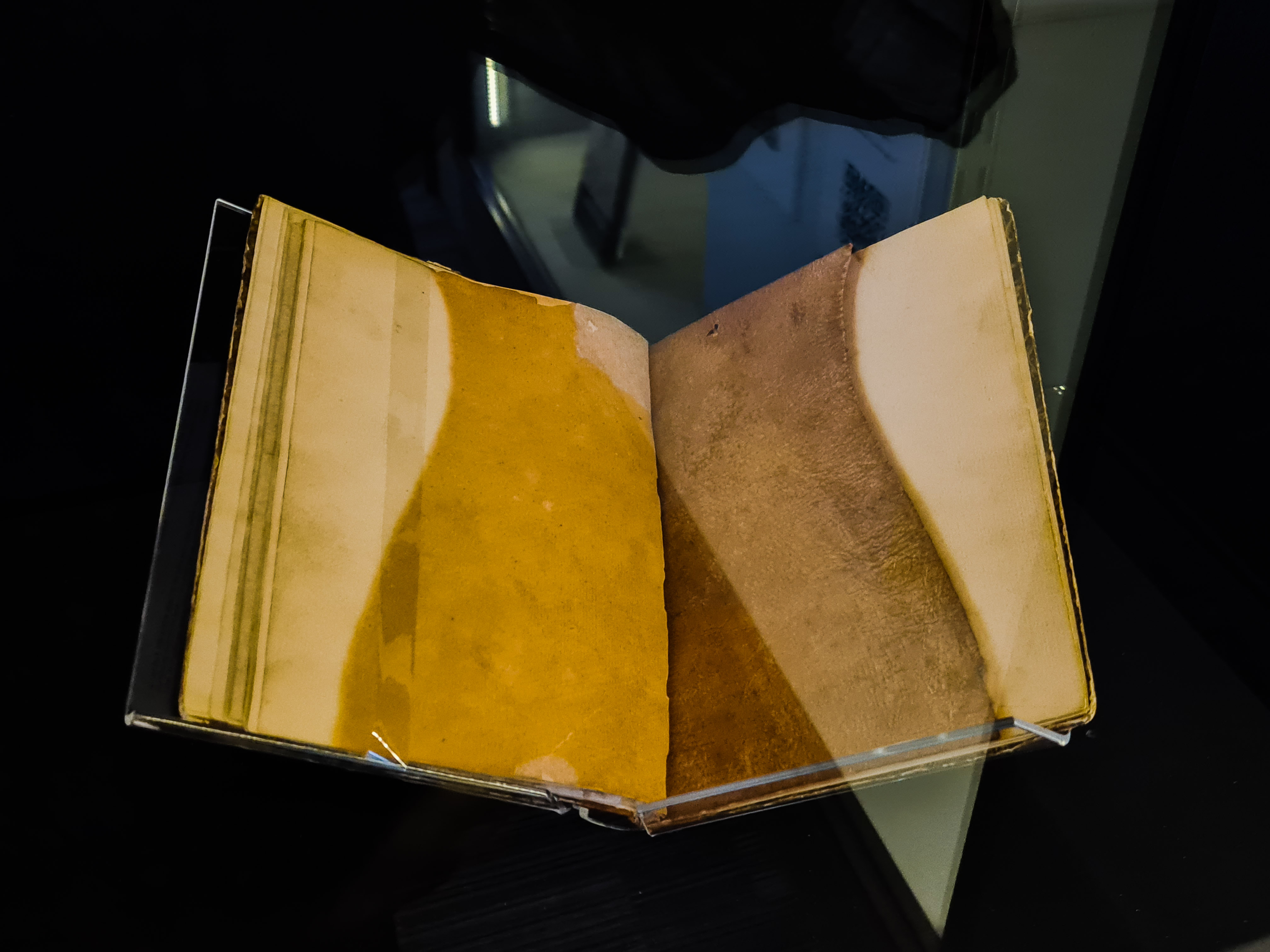

Longespée’s tomb is in my opinion an extremely beautiful one. Sculptured in the Gothic style[14], the altar is made of wood with a marble recumbent figure lying on top. William looks to his right and the effigy is remarkably lifelike. He wears chain mail, a military cloak and a flat headpiece. Only his eyes and nose are visible. His head rests on a pillow. In his left hand, he holds a shield showing seven lions, the coat of arms of his grandfather. The edge of the slab is decorated with English trefoil foliage. Both the altar and figure would have originally been brightly coloured (traces of the paint can still be seen) and gilt. Who would have thought that such a peaceful image could have hidden such a dark secret?

PART TWO: Arsenic, a Rat and a Skull

A Natural Death?

The discovery of the rat led many people to surmise that Longespée had in fact been murdered. Those that accepted this supposition then turned their attention to who could have been responsible and why. One possibility could have been jealousy. Someone at court might have been envious of Longespée’s power and authority – he had after all become even more prominent in Henry III’s court after the death of William Marshal. Unfortunately, there is virtually no evidence to support such a hypothesis with the exception of a comment made by Roger of Wendover in his work, the first Flores Historiarum. In his account Roger of Wendover points the finger at the influential Hubert de Burgh, accusing him of poisoning Longespée[15].

So, what would have been de Burgh’s motive? De Burgh rivalled (and possibly exceeded) Longespée for political influence.[16] Could he have wanted to become even more powerful or was there another reason why de Burgh wanted Longespée out of the picture? One theory that has also been put forward is that during Longespée’s sojourn with the monks at the Île de Ré, he was believed to be dead and that de Burgh took the opportunity to try to win the hand of his ‘widow’ Ela[17]. His plans were destroyed by the arrival of the very much alive Longespée, de Burgh exacted his revenge and murdered him. On the surface this story could sound plausible, casting a greedy and morally corrupt de Burgh into the role of arch-villain, but on looking at it in more detail there is one significant problem. At the time de Burgh was married to Margaret, the sister of Alexander II, King of Scotland[18]. Was he planning to win Ela and then murder his wife? It seems unlikely and it is strange that there is only one mention of de Burgh as a murder suspect. Surely if the uncle of the king died in suspicious circumstances it wouldn’t have gone unnoticed! In any event, even after Longespée’s death, Ela did not remarry. She was awarded the title of Sheriff of Wiltshire, a role she held for two years before retiring from the world to Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire (an abbey she founded) in 1238, becoming its Abbess in 1261[19].

Arsenic and Medicine

Another possible reason for the presence of arsenic in Longespée’s body is that the arsenic had been ingested or absorbed long before he died. Arsenic as both a poison and a medicine has been in use since antiquity. Indeed, the Greeks used arsenic to treat ulcers and abscesses[20] and many apothecary shops would stock arsenic as a matter of course. Arsenic was used in a variety of ways and in different quantities according to the illness or disease as well as a “corrosive for treating wounds of people and animals”[21]. When Longespée arrived at Île de Ré after the shipwreck he could have been severely injured and very ill. Maybe the monks healed him using an arsenic-based treatment and maybe he was accidentally given too much. We will never know but it is definitely a theory that should be taken into consideration.

A Poisoned Rat

There is another plausible scenario. Could it be that Longespée hadn’t been poisoned at all but that it was the rat that had ingested the poison? At the time of Longespée’s burial, Salisbury Cathedral had not been completed. Material used in the construction of the cathedral including paints could have contained arsenic. The rat could have chewed on something containing the poison and then managed to get into the tomb with Longespée whilst his remains were being interred. The rat could have then eaten Longespée’s head – a grisly thought to be sure – and got into the skull where it subsequently died. Such a hypothesis is perfectly plausible. If you wish to see the rat for yourself, its remains are today displayed at Salisbury Museum.

Final Thoughts

Although believing that Longespée was murdered adds an air of mystery and romance to his story, in my opinion, I think that it was more likely that the rat somehow managed to get into his tomb. There is just not enough evidence to support the poisoning claim, although much depends on how reliable you view Roger of Wendover as a source. Most modern historians do not have a high opinion of his trustworthiness, with an entry in the 1911 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica stating that “Wendover is a copious but inaccurate writer…Where he is the sole authority for an event, he is to be used with caution.”[22] With that word of warning ringing in your ears, I leave you to make up your own mind on the mystery of the tomb of William Longespée.

A special thank you to the staff of Salisbury Cathedral for their help.

Bibliography:

Nick Barratt, The Restless Kings: Henry II, his sons and the wars for the Plantagenet crown, Faber & Faber, 2019

Notes:

[1] Salisbury: The liberty of the close https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol6/pp72-79

[2] William Longsword, 3rd earl of Salisbury, https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Longsword-3rd-earl-of-Salisbury

[3] William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Longesp%C3%A9e,_3rd_Earl_of_Salisbury

[4] William Longsword, 3rd earl of Salisbury

[5] Nick Barratt, The Restless Kings: Henry II, his sons and the wars for the Plantagenet crown

[6] Lady Nicholaa de la Haye, http://magnacarta800th.com/schools/biographies/women-of-magna-carta/lady-nicholaa-de-la-haye/

[7] William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury

[8] Ibid

[9] Nick Barratt, The Restless Kings: Henry II, his sons and the wars for the Plantagenet crown

[10] Ibid

[11] William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury,

[12] William Longespee, 3rd Earl of Salisbury, Tomb of William Longespee – Salisbury Cathedral | Professor Moriarty (professor-moriarty.com)

[13] William Longsword, 3rd earl of Salisbury,

[14] Tomb of William Longespee; Earl of Salisbury. Detail of head, worldimages.sjsu.edu/objects-1/info/38914

[15] William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury,

[16] Hugh de Burgh, 1st Earl of Kent, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hubert_de_Burgh,_1st_Earl_of_Kent

[17] William Longsword, 3rd earl of Salisbury,

[18] Margaret of Scotland, Countess of Kent, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_of_Scotland,_Countess_of_Kent

[19] William Longsword, 3rd earl of Salisbury

[20] Arsenic: medicinal double-edged sword, https://www.healio.com/news/hematology-oncology/20120325/arsenic-medicinal-double-edged-sword

[21] Murder by Poison: A Crime from 15th century Valencia, https://www.medievalists.net/2020/03/murder-by-poison

[22] Roger of Wendover, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1911, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Roger_of_Wendover

Image attributions

Salisbury Cathedral: Andrew Dunn, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Salisbury_Cathedral.jpg, via Wikimedia Commons

William Longsee: By Thomas Andrew Archer, Charles Lethbridge Kingsford – The crusades; the story of the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11921405

Detail of a miniature of Philip Augustus awaiting his fleet: Master of the Cambrai Missal, File:Philippe Auguste attendant sa flotte.jpg – Wikimedia Commons Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

William Longspee’s Tomb: Hugh Llewelyn from Keynsham, UK, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Leave a Reply